LBWF Director of Governance and Law Mark Hynes releases his asbestos report and finds LBWF to have acted lawfully, but it’s not the final word

In September 2022, I asked the council’s Director of Governance and Law, Mark Hynes, to confirm that, in the period 2015-20, LBWF had managed asbestos in the Town Hall as required by the key piece of legislation, the Control of Asbestos Regulations 2012 (hereafter CAR 2012).

I was particularly concerned about the Town Hall basement, where asbestos was known to be most prevalent, and wanted to establish that LBWF had learned the lessons of its 2015 conviction for exposing staff and contractors who had used the basement to dangerous asbestos dust.

A few days ago, 10 months after he agreed to investigate, Mr. Hynes finally released a report of his findings.

This post looks at his argument and evidence, before briefly turning to consider the legal input of his two paid advisers, Clyde & Co. LLP and Richard Matthews KC.

Mr. Hynes argument and evidence

In short, Mr. Hynes’ judgement is that LBWF did uphold CAR 2012.

He concedes that LBWF’s overarching Asbestos Management Plan (AMP) was not updated after 2013, as it should have been, and lacked important detail.

But he believes that this did not matter, because all the while LBWF was placing various asbestos-related documents (which he lists) on its ‘Property Services asset management database “Concerto”’, and by doing so ensured compliance.

This is an apparently authoritative finding, but whether it stands up to scrutiny is in fact far from certain, as the following paragraphs demonstrate.

Since in a voluminous correspondence with me lasting eleven months, Mr. Hynes never once mentioned Concerto, it deserves some explanation.

Mr. Hynes notes that Concerto is cloud-based, and continues:

‘the Town Hall is specifically identified (which includes the Town Hall and War Memorial and other buildings that are part of Fellowship Square) and there are over 2500 documents recorded in the system against Fellowship Square.

There are then a number of subfolders where documents can be electronically deposited, and Asbestos [sic] is identified….

The subfolder on asbestos re-inspections clearly satisfies the Regulations [CAR 2012]…

Furthermore, the system has records of all the remedial action taken following any new asbestos being identified…’.

Mr. Hynes adds, without further comment, that Concerto was ‘accessed by building managers’.

All this may seem persuasive, but there are several necessary qualifications. First, Mr. Hynes on occasion appears less than certain about the true scope of Concerto’s content, for example hedging his bets by observing ‘Concerto had an asbestos folder for the Town Hall with what appears to have been a comprehensive set of entries [emphasis added]’.

Second, he admits that LBWF’s use of Concerto was deficient, first observing ‘Concerto also has a red box facility which identifies which documents need to be reviewed with a date. The system actually flags up the actions needed to be taken’, but then acknowledging ‘It appears no one was using this element of Concerto to identify that the AMP of 2013 had not been reviewed and updated’.

Third, and more surprising still, Mr. Hynes also lets slip that Concerto has actually only been ‘properly implemented’ in the last year or so, a big admission given the importance he places on it in his overall argument.

Finally, though, as noted, Mr. Hynes asserts that ‘building managers’ accessed Concerto, he provides no evidence that this actually happened, let alone how often, and in what circumstances, thus overlooking the obvious point that possessing a cloud-based database is one thing, regularly consulting it quite another.

Beyond Concerto, there are four other sets of problems with Mr. Hynes’ report, which can be grouped under the following headings.

Asbestos surveys

Mr. Hynes makes much of the fact that the frequent asbestos surveys of the Town Hall, which LBWF commissioned from 2013 to 2020, are logged on Concerto, seeing this as prime evidence of compliance, but he nowhere discusses the surveys’ contents, which is a serious mistake.

Examining the surveys reveals that they were compiled by five different firms (GBNS in 2012, Spectra in 2013, Clearway in 2016, ALS in 2017; GBNS in 2018 and 2019; and Environtec in 2020); no firm took exactly the same approach; the numbering system used to identify the basement’s rooms and corridors could vary from survey to survey; and on occasion LBWF failed to provide definitive drawings, meaning that in one case, at least, ‘the [firm’s] surveyor did a sketch’ and annotated it ‘at time of the survey’.

Furthermore, the surveys were of different types, with very rigorous and intrusive refurbishment surveys, aimed at identifying all the asbestos that was present, completed in 2012 and 2020; standard management surveys, aimed at assessing the condition of known asbestos locations, completed in 2013, 2016, and 2018; and simple visual re-inspections completed in 2017 and 2019.

The upshot is that trying to compare the surveys would have been difficult at the time, and remains so today.

However, all that accepted, analysing the surveys in sequence is worthwhile, and in the end very concerning, as the following summary of their findings for the Town Hall basement demonstrates.

In 2012, the refurbishment survey emphasised ‘the large scale of asbestos contamination within the basement floor’, and the fact that asbestos ‘dust and debris’ had been found ‘throughout the area of the survey’; and went on to list 53 specific locations where asbestos was present, 42 involving ‘high hazard materials’.

Subsequently, in the years down to 2019, the management surveys and re-inspections largely focused on a relatively small sample of locations – 26 in 2017, for example – where asbestos had been previously identified. Taken together, they showed that asbestos was certainly still present in the basement, but suggested that it was under control, in fact to some extent declining in importance, as LBWF completed planned remediation work.

However, in September 2020, while preparing for the complete renovation of the Town Hall, the second very thorough refurbishment survey revealed that, whatever LBWF’s previous remediation, and the assessments of recent surveys and reinspections, the asbestos in the basement remained pervasive, this time found in 135 specific locations, 17 ‘high risk’ and 66 ‘medium risk’, some involving ‘debris to floor’.

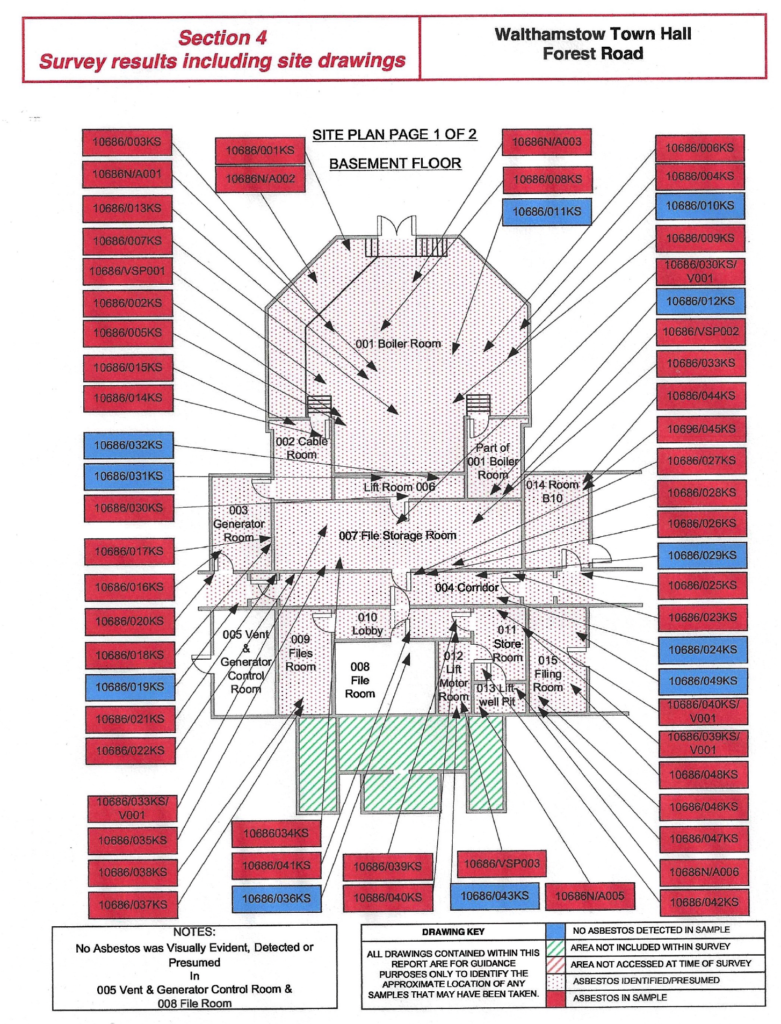

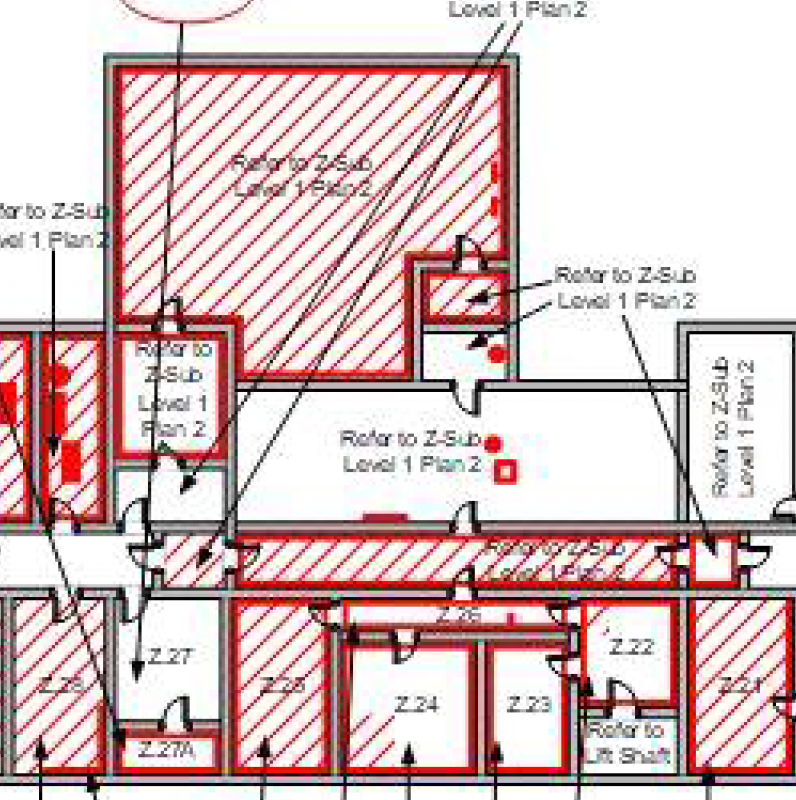

Placing drawings from the 2012 and 2020 surveys next to each other illustrates the degree of continuity. For example, here are two close ups of the central basement area, with the presence of asbestos marked in red:

IMAGE

2012

2020

On the basis of the evidence, therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that the basement was replete with potentially dangerous asbestos continuously through to 2020.

This being the case, it is imperative to ascertain exactly who – if anybody – might have had their health jeopardised.

Mr. Hynes, predictably, avoids considering this issue at all. However, there is a small amount of relevant data.

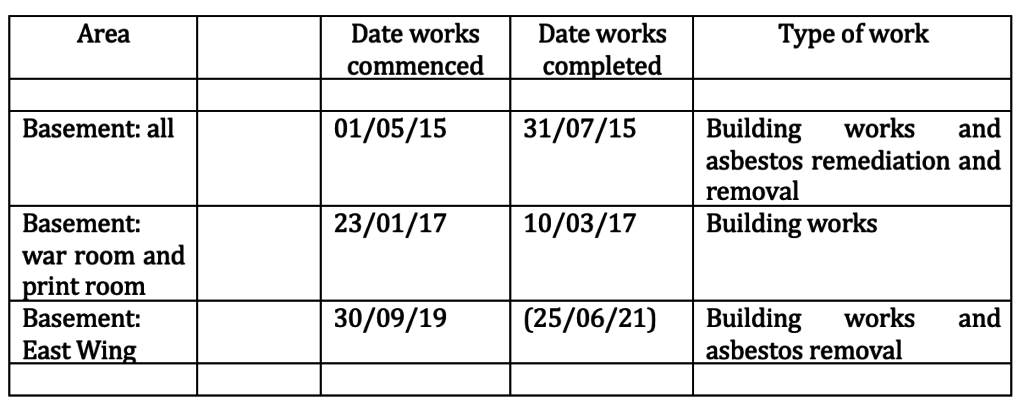

Questioned under the Freedom of Information Act, LBWF states that from 2015 onwards the basement was either fully or partly closed for construction work on three occasions:

So although it appears that LBWF did not record names and numbers, it is certain that on each occasion, a fair number of construction workers were onsite.

In addition, the only asbestos survey which looks at ‘human exposure potential’, that of 2018, shows that four rooms in the basement, plus the main corridor, were being used, though ‘infrequently’.

Such evidence may be indicative, but it is not, of course, conclusive. What’s unarguable, though, is that staff and contractor footfall in the basement continues to be a very important issue, and it is a glaring weakness of Mr. Hynes’ report that he ignores it.

Training

The CAR 2012 requires that ‘Every employer must ensure that any employee employed by that employer is given adequate…training where that employee…is or is liable to be exposed to asbestos’, and such training must be ‘given at regular intervals’.

However, as Mr. Hynes’ report shows, LBWF now struggles to prove that after 2015 such training has occurred.

In his discussion of training, Mr. Hynes begins by acknowledging that when in March 2023 I used the Freedom of Information Act to ask about it, LBWF could not produce anything relevant.

But since then, he reports, ‘the Council has evidenced attendance by building managers on a Health and Safety course, which did cover Asbestos [sic] and their duties which took place in 2013/14 and 22 delegates attended’.

In addition, he notes: ‘Asbestos Awareness training was provided in 2018, but only schools attended’, and ‘Since 2019 the Asbestos Awareness Training has been made available…however the training is voluntary and (in part) due to the pandemic, the Council cannot evidence which staff attended the course’.

Although Mr. Hynes is apparently oblivious to the fact, these snippets prove little or nothing. How he squares them with the requirements of CAR 2012 is unclear.

Permits to Work

Between 2015 and 2020, LBWF insisted that before any asbestos related work could begin, ‘premises managers’ and contractors must read and sign a permit to work (PTW) form.

This, it was explained, constituted ‘a formal control system aimed at the prevention of accidents’, by making signatories actively confirm that they knew where asbestos was located, agreed on the work to be done, had comprehensively risk assessed, were familiar with emergency procedures, etc..

So, having found out, as already related, that LBWF had hired contractors to work in the basement on three occasions between 2015 and 2020, in December 2022 I used the Freedom of Information Act to ask for the completed PTW forms.

After 112 days, and the intervention of the Information Commissioner, LBWF finally admitted that ‘the Council does not hold the information that you requested’.

Significantly, Mr. Hynes report provides no further elucidation. His list of key documents on Concerto references one PTW for 2014, but none for 2015 to 2020. Little wonder that in the text of his report, Mr. Hynes avoids discussion of the subject altogether.

The complaint to the HSE of January 2020

On 13 January 2020, the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) informed LBWF that a complaint had been made about construction work in the Town Hall basement, which it summarised thus:

‘Drilling in the basement is causing a lot of brick dust to go out throughout the buildings, so much that it is setting off the fire alarms; and

With the presence of asbestos in the basement, there is risk to possible exposure to asbestos particles in the brick dust produced by the drilling’.

Was LBWF in charge of the site, the HSE asked, or was it being run by a ‘principal contractor’?

By return, LBWF confirmed that a ‘principal contractor, ‘Purdy’s’ [Purdy Contracts Ltd.], was running the site; provided a contact name; and forwarded ‘a draft Management Procedures and Protocol document’ for comment.

A day later, LBWF’s Head of Health and Safety, David Garioch, reassured the HSE further, reporting that an internal ‘Health and Safety Team’ investigation of the previous week ‘[had] not identified any asbestos issues, as the basement was fully stripped of Asbestos [sic] several years ago’.

Accordingly, the HSE inspector took no further action about asbestos (though he/she did object to the fact that a mask-less worker in the basement was seen sweeping up concrete dust with a broom, yet without the water suppression mechanism being turned on!).

The episode described is not mentioned in Mr. Hynes’ report, and when I recently asked him about it, he seemed vague.

However, material disclosed to me shows that LBWF did not dispute the basic facts about what happened, so what’s left to explain is why the ‘Management Procedures and Protocol document’ was still in draft even though work had started; why LBWF cannot produce the relevant PTW; and – most important, by far – why Mr. Garioch told the HSE that the basement had been ‘fully stripped’ of asbestos ‘several years ago’, when, as the preceding discussion shows, that was at odds with the survey evidence.

It goes without saying that Mr. Garioch would not try deliberately to deceive the HSE, so why he wrote as he did remains unresolved. One possibility is that he was merely repeating what building managers had told him, which does not inspire confidence that documents uploaded to Concerto were necessarily being read.

The legal advice provided by Clyde & Co. LLP and Richard Matthews KC

Mr. Hynes acknowledges that, in drawing up his report, he has received advice on ‘technical legal elements’ from ‘global law firm’ Clyde & Co. LLP (fresh from a bruising encounter with no less than the US Department of Justice) and Richard Matthews KC, neither coming cheap.

Clyde and Co. LLP is a specialist in providing the ‘highest quality advisory and dispute resolution services to insurers and their clients’.

Mr. Matthews led LBWF’s defence team at the 2015 trial, for which he received a payment of £50,000.

It is unknow how much public money has been expended in this case – the sum was promised but has yet to be released.

Quite why Mr. Hynes felt it necessary to bring in such expensive help is unexplained, but there may be an element of trying to discourage future litigants, especially as LBWF recently has been forced to pay out £265,000 plus private medical and legal costs to an ex-Town Hall employee who, in its service, had contracted a cancer linked to inhaling asbestos fibres (his solicitor commenting ‘“I think this is the worst example of neglect of asbestos in a public building that I have seen in 30 years”’).

However, one fact should not be forgotten.

Clyde & Co. LLP and Richard Matthews KC have offered Mr. Hynes an opinion, but it is just that, an opinion.

Other legal experts will offer other opinions.

And anyway, not all the evidence about Town Hall asbestos has so far emerged.

In plain English, Mr. Hynes’ report is by no means the final word.

Mick Holder - July 27, 2023, 5:40 pm

Whilst anyone can have an opinion about legality, until it is tried and tested in a court of law it remains just that – an opinion. LBWF must not be allowed to mark their own homework on such an important issue. In my opinion, given the evidence Mr Tiratsoo has so doggedly uncovered and given LBWF’s previous asbestos failures and fine, far from self declared innocence, LBWF should face further charges in court.

It is highly likely that this situation is being repeated in a sizeable number of other authorities and circumstances around the country. The persistently high asbestos disease deaths give evidence to asbestos management failures. Sadly, what’s probably not happening elsewhere is the oversight of someone like Mr Tiratsoo.