LBWF opts for worthless ‘unconscious bias training’, while long-term staff recruitment and reward inequalities remain in place

In recent months, LBWF has employed third parties to put about 1,600 of its staff through unconscious bias training (UBT).

Some will no doubt applaud, seeing this as a firm step forward in the fight against racism and discrimination.

However, such commendation is more than a little misguided.

UBT is certainly in vogue, and at present there is an increasingly influential cohort of HR professionals, private sector ‘trainers’, and campaigners who benefit from pushing its supposed efficacy.

However, when the hype and self-promotion are stripped away, the flaws in UBT become very obvious indeed, to the extent that there is major doubt as to whether it has any value whatsoever.

No-one, of course, denies that unconscious bias about ethnicity (as about other matters) exists. But what the scholarly literature shows is that (a) reliably identifying and measuring such bias is very difficult; and (b) evidencing that it fashions real world behaviour is more difficult still.

Given these by now well-established findings, it is unsurprising to discover that rigorous studies which attempt to assess the impact of UBT in this context inevitably are downbeat. For example, an Equality and Human Rights Commission report of 2017 found that ‘The evidence for UBT’s ability effectively to change behaviour is limited’, and several other subsequent academic studies have come to even more damning conclusions.

Needless to say, criticising UBT is not to suggest that LBWF should just twiddle its thumbs when it comes to how it recruits and values staff from different backgrounds. Indeed, a brief survey of the evidence suggests quite the contrary.

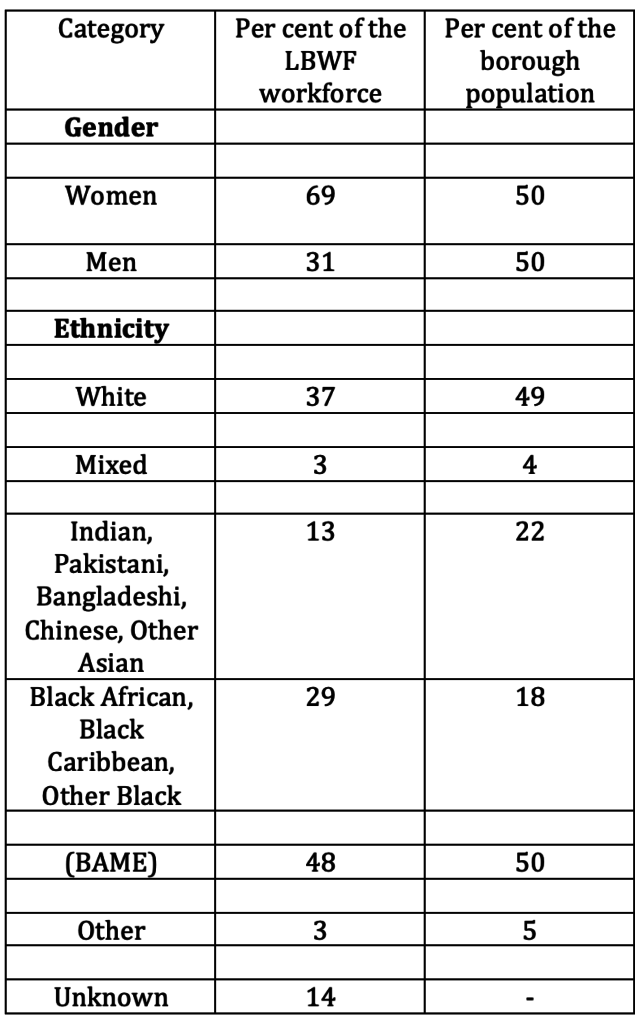

The standard method of evaluating whether a workforce is appropriately diverse involves benchmarking it against the composition of the local population. Applying this test to the Town Hall produces the following results:

What emerges is that women are unarguably over-represented, and the ‘Black’ sub-group probably so, while for the ‘White’ and ‘Asian’ sub-groups the opposite seems to be true (more precise conclusions are impossible because of the large number of employees whose ethnicity is said to be ‘Unknown’).

Turning to the detail of remuneration adds to the concern.

Data for 2015 and 2020 shows that despite their numerical weight BAME staff make up only a paltry 20 per cent of the top 5 per cent of council earners.

Worse still, at the other end of the spectrum, while LBWF has a gender pay gap which is double the size of the UK borough average, in itself reprehensible, Asian and Black women do especially badly, with a 2019 survey showing them earning on average £14.21 and £14.66 per hour, respectively, well below the figure for their White counterparts, £17.10.

What makes these various disparities all the more unacceptable is that they are visible, well documented, and longstanding, in fact largely untouched by a decade or so of outright Labour control in the Town Hall.

The lesson, surely, is that rather than worrying about quackery like UBT, what Cllr. Coghill and her Cabinet colleagues need to do is start from the established facts which stare them in the face, and concentrate on introducing realistic but robust policies which will bring about change.