Hate crime in Waltham Forest update: LBWF and the police still treat it as a key priority, but the facts don’t support them

In February 2023, a post on this blog examined hate crime in Waltham Forest, and queried why LBWF and the local police force was treating it as a key priority, worthy of enhanced financial and administrative support (see links, below).

What follows looks at what has happened subsequently. Hate crime has continued to be prioritised. But are the doubts of earlier years also still present?

First, a summary of the basic evidence.

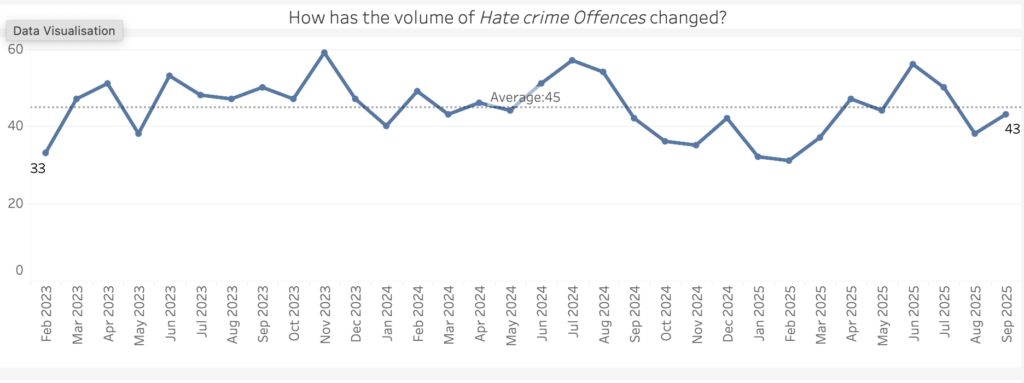

The only comprehensive series about hate crime is data collected by the police, and for the period February 2023 to September 2025 for Waltham Forest this reveals the following.

(a) The volume of recorded hate crime has varied, with peaks and troughs, but there is no discernible upward trend over time, as this graphic illustrates:

(b) On average, 45 hate crimes have been recorded every month.

(c) Of the 1,437 hate crimes recorded in total, the great majority are classified as ‘Racist and Religious’ or ‘Racist’, with those classified as specifically ‘Homophobic’ and ‘Islamophobic’, often assumed to be the most prevalent and damaging, being 174 and 136 respectively.

(d) In context, hate crimes constituted 2 per cent of all the crimes recorded, with, for comparison, ‘Theft’ and ‘Violence Against the Person’ each making up no less than 25 per cent of the total.

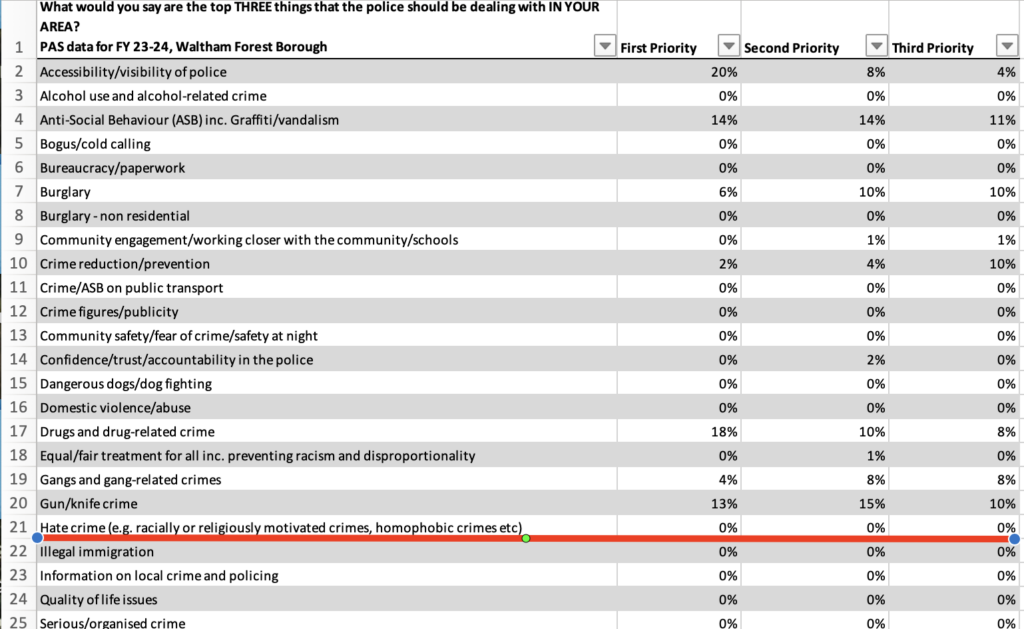

Turning to residents’ views on these matters, the Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime (MOPAC) carries out an annual survey of London boroughs which asks those polled for the ‘top THREE things that the police should be dealing with IN YOUR AREA’, and for the Waltham Forest sample hate crime is rarely, if ever, cited, the 2023-24 survey being fairly typical:

It would appear, therefore, that in recent years, hate crime has continued to be neither a volume crime, nor something that the public is especially worried about.

However, that accepted, it’s also worth exploring whether LBWF and the police’s chosen approach has actually worked on its own terms, that is, has led to the successful prosecution of hate crime perpetrators, and thus acted as a deterrence.

There being no available record of borough level court cases dealing with hate crime, the source which is most useful here is a response that the police have recently provided after questioning Under the Freedom of Information Act.

This traces what happened to the 1,637 hate crimes in Waltham Forest which were recorded by the police between January 2022 and November 2024, and reveals that only 8 per cent of the total resulted in a charge or summons, while all the rest were dropped, mostly because of evidential difficulties.

It’s true that other types of offence have similarly poor outcome ratios.

But given that hate crime in Waltham Forest has been so high profile, it’s certainly a surprising finding. A good deal of police and council time seems to have been expended achieving only very modest returns.

How has this situation arisen?

It’s worth noting first that the official guidance used by the police on hate crime includes the following:

‘Where the victim, or any other person, perceives that they have been targeted because of hate or hostility against a monitored or non-monitored personal characteristic, the crime should be recorded and flagged as a hate crime…

At the time of reporting, the victim or person reporting does not have to justify or provide evidence of their perception that the crime was motivated by hostility. Officers and staff should not challenge this initial perception’ [emphasis as in the original].

This is an unusual approach, and it’s fairly obvious that it may inflate police statistics on the incidence of hate crime, while doing little to safeguard against claims that later turn out to be weakly evidenced or even false.

To make matters worse, LBWF and police public messaging sometimes has suggested that the definition of what constitutes hate crime is more encompassing than it actually is.

For example, addressing a council scrutiny committee, a local police inspector referred to misogyny as a hate crime.

He was (and remains) incorrect, but it is significant that those present did not query what had been said, and in fact seem to have accepted it as gospel (see links, below).

Similarly, material presented to the much praised LBWF’s Citizens Assembly on Hate Crime included slides which seem to blur the line between behaviours which are unpleasant but not illegal (sometimes called ‘hate incidents’) and behaviours which are unarguably criminal.

Put in a nutshell, when the police are tasked with investigating something as nebulous as, say, ‘being talked down to’ (one of the examples used on the slides) and then establishing whether or not this is ‘an act of victimisation’, it’s surely unsurprising that so many alleged hate crime investigations flounder on ‘evidential difficulties’.

In the light of the foregoing, it’s certainly difficult to believe that the emphasis put on hate crime in Waltham Forest has ever been based only upon a calm appraisal of the facts.

Might it be that politics has to some extent intruded?

Might it be, say, that the focus on hate crime is a handy way of responding to, and cultivating support from, the various community leaders and pressure groups whose existence depends upon the insistence that their clientele are victims, perpetually under threat from the great unwashed?