Hate crime in Waltham Forest: setting aside the scary rhetoric, is it as bad as LBWF claims?

Introduction

In the last few years, LBWF has regularly asserted that Waltham Forest is afflicted by ‘an unprecedented rise’ in damaging hate crime – especially, according to senior councillors, racist, Islamophobic, homophobic, anti-Semitic, and transgender hate crime.

As a response, and leading on from a specially convened Citizen’s Assembly, it has put in place various high-profile awareness, intervention, and training programmes, costing hundreds of thousands of pounds.

With the Town Hall’s example before it, the local police force has followed suit, employing a dedicated hate crime officer; offering ‘an anonymous email inbox…for those experiencing hate crime’; mounting patrols at ‘identified hot spots’; engaging with ‘communities groups [sic], faith groups and the LGBT+ community’; ‘revisiting all previous reports to see if hate crime had been a factor’; and ‘monitoring social media to keep an eye on any trends’.

Little of this has attracted much scrutiny, primarily because it appears that LBWF and the police are merely swimming with the tide, dutifully responding to Mayor Khan’s decision to make hate crime a priority, and urged on by the host of consultants and political activists who are in business to offer advice.

Yet, amidst all the fervour, one fundamental question seems to have been overlooked. Hate crime in the area is a blight, the mantra goes, and must be addressed as a matter of urgency. But is this really true? To be more precise, are the expensive measures that have been put in place fully justified by the evidence?

Definitions and data

As a starting point, it is sensible to look at how hate crime is currently defined, and the data which are available to measure it.

The police and Crown Prosecution Service advises that a hate crime is any criminal offence ‘which is perceived by the victim or any other person, to be motivated by hostility or prejudice, based on a person’s disability or perceived disability; race or perceived race; or religion or perceived religion; or sexual orientation or perceived sexual orientation or transgender identity or perceived transgender identity’.

An explanatory note adds that since there is no legal definition of ‘hostility’, ‘we use the everyday understanding of the word which includes ill-will, spite, contempt, prejudice, unfriendliness, antagonism, resentment and dislike’.

For its part, LBWF advises that the range of criminal behaviours which constitute hate crime includes ‘physical and verbal abuse, threatening behaviour or harassment or damage to your property’ and also ‘being treated as if you are stupid, talked down to, being ignored, avoided, stared at or being rudely treated because of who you are or who you are perceived to be’.

Turning to data, the major source is the monthly series on hate crime that the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) has collected and published in common format for all London boroughs since January 2018, and this requires some brief elucidation.

The MPS series is unique because it’s the only one that goes beyond purely national figures. But it is also easily misunderstood.

The key point to stress is how the MPS defines hate crime.

The MPS is not referring to instances where a conviction has been secured, or a caution issued.

Rather, it is referring to instances where a complainant reports that a third party has used words, or exhibited behaviour, of the type described above.

And here, it is the voice and judgement of the complainant which is held to be paramount. Indeed, the official advice to officers states: ‘The victim does not have to justify or provide evidence of their belief, and police officers or staff should not directly challenge this perception. Evidence of the hostility is not required for an incident to be recorded as a hate crime. A crime should be recorded as a hate crime…if it is perceived by the victim or any other person to be motivated by hostility’.

With these various observations in mind, the following eight sections present some key findings, the first five about the dimensions of hate crime in Waltham Forest, the following three about matters of context.

Hate crime in Waltham Forest (1) volume over time

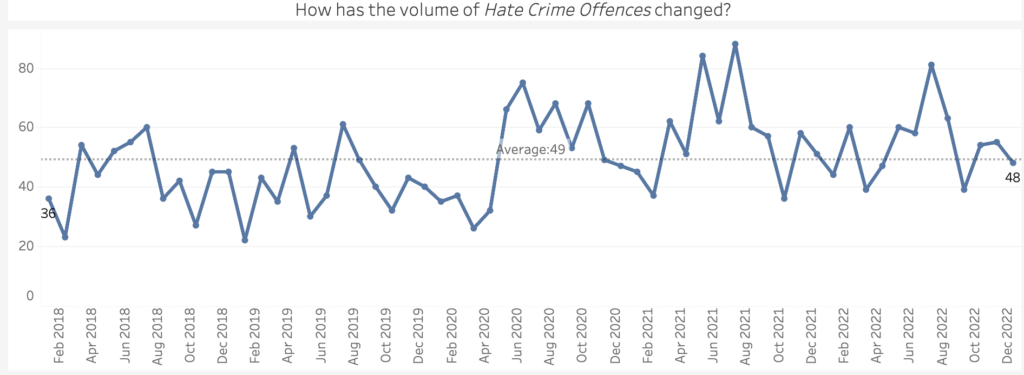

The monthly MPS hate crime figures for Waltham Forest between January 2018 and December 2022 are illustrated thus:

It is immediately evident that there has been an increase over time, albeit with peaks and troughs.

However, whether the trend reflects more hate crime per se, or greater enthusiasm to report it, perhaps encouraged by LBWF and police publicity, remains unclear.

It is also worth underlining that the totals across this period always have been comparatively small, illustrated by the fact that even in the worst year for hate crime, 2022, while an average of 54 such crimes were recorded each month, the equivalent figure for violence against the person, to take one example, was 564, i.e., more than ten times greater (for further discussion of this point, see below).

Hate crime in Waltham Forest (2) character

The MPS breaks down the total number of hate crimes into eight different categories, but also cautions that ‘A crime can have multiple Hate Crime flags added to it’, meaning that ‘Totals for the distinct categories of hate crime should NOT be summed together as this will result in double counting’.

This caveat accepted, it is clear that 80 per cent or more of MPS recorded hate crime in Waltham Forest for the period 2018 to 2022 involved ‘race’, while the totals for ‘homophobic’, ‘Islamophobic’, and ‘transgender’ hate crime were significantly lower, making up perhaps 12 per cent, 7 per cent and 1 per cent of the total respectively.

Hate crime in Waltham Forest (3) perpetrators and victims

There is relatively little information in the public domain about the borough’s perpetrators of hate crime, the exception being a presentation made by a police inspector to councillors which covered the period February 2021 to January 2022.

This showed that the majority of perpetrators were men, with all age groups represented.

As to ethnicity, the MPS failed to record anything in about a third of cases, and allotted the rest to six categories, revealing that 46 per cent of perpetrators were ‘White European’, 27 per cent were ‘Afro-Caribbean’, 20 per cent were ‘Asian’, and 6 per cent were ‘Dark European’, with ‘Arabian/Egyptians’ and ‘Orientals’ making up the balance.

Comparing these figures to the ethnic makeup of the wider population is hazardous because of differences in classification, but it appears that the distribution of perpetrators was broadly proportionate to each ethnic group’s overall size.

Regarding victims, there does not appear to be any specific information for Waltham Forest available, though the MPS data noted in the previous section are suggestive in non-race cases.

Hate crime in Waltham Forest (4) outcomes and criminal proceedings

One important and sometimes overlooked question is what happens after the police record a hate crime, and whether any further action, principally the issuing of a caution or summons, follows.

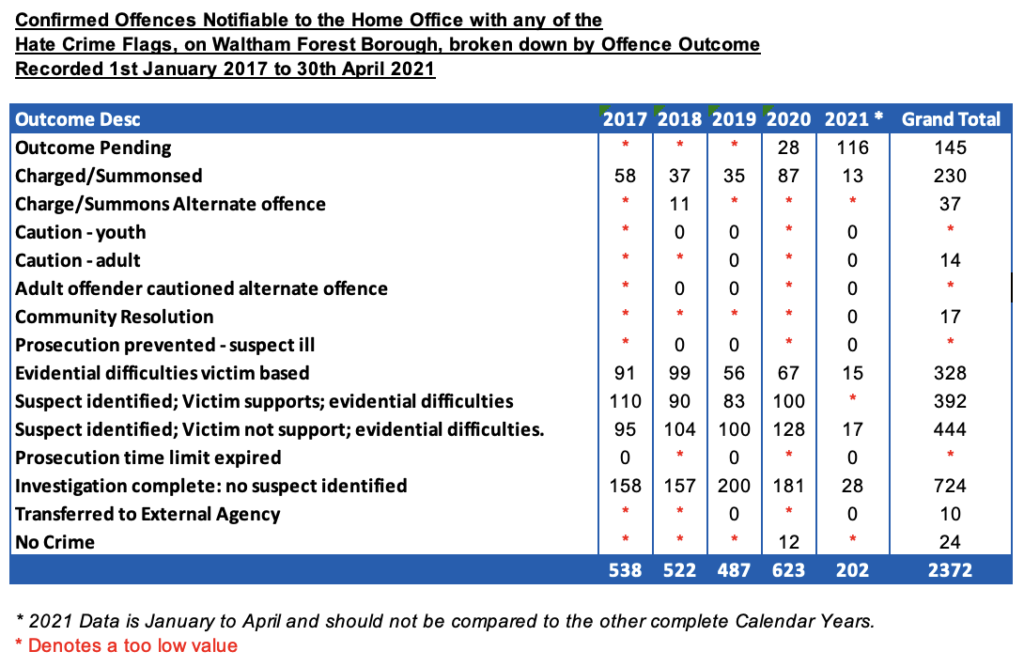

It appears, again, that borough level figures over time are not generally available, but in answer to a Freedom of Information Act inquiry, the MPS has supplied a snapshot for Waltham Forest, covering January 2017 to April 2021:

This reveals that in 86 per cent of the 2,217 cases where there was a known outcome, the police decided not to proceed further, either because of evidential difficulties, or because no suspect was identified, or because no crime had been committed.

The bottom line is that the cases where the police did take action constituted only a small proportion of the total, about 13 per cent.

It is worth adding, however, that issuing a summons and gaining a conviction are two different things, and it is quite possible that a proportion of those who appeared in court were acquitted.

Hate crime in Waltham Forest (5) impact

According to the politicians and professionals involved in pushing hate crime up the agenda, it’s an exceptionally damaging type of crime, and this is the reason why it should always be treated as a priority.

So, do Waltham Forest residents agree?

As a starting point, it’s worth noting that the Citizen’s Assembly was evangelic about hate crime’s perniciousness (asserting that it produced fear, disempowerment, isolation, and anger, as well as creating ‘marginalisation and division in the community’) and so certainly agreed it needed to be treated with urgency.

In passing, it is unclear what logic was being used here, because of course many crimes against the person, for example mugging and sexual harassment, cause almost exactly the same kinds of harm.

However, putting that point to one side, it is questionable whether anyway the Citizen’s Assembly’s views were, and are, widely shared elsewhere in the borough.

For while LBWF research shows that many are familiar with the idea of hate crime, other evidence indicates they are not convinced of its overwhelming importance.

In 2019, polling revealed that the crimes which residents ‘most worried about’ were burglary, knife crime and drug dealing, while three years later, when the Institute of Health Equity (IHE) ran focus groups, its findings were very similar.

Fear of crime, the IHE reported, was ‘a serious problem in Waltham Forest’, and when it asked why, respondents provided examples which ‘ranged from intimidating groups of young people hanging around on the street to drug dealing and taking on the streets, street drinking, and in some cases personal experience of knife crime and mugging’.

Hence, it appears that, despite all the clamour about hate crime, for the majority, the most burning issues, the ones which really impinge on their lives, lie elsewhere.

Context

So much for the dimensions of hate crime in the borough. The following paragraphs round out the picture by providing some context.

(1) hate crime v. all crime in Waltham Forest

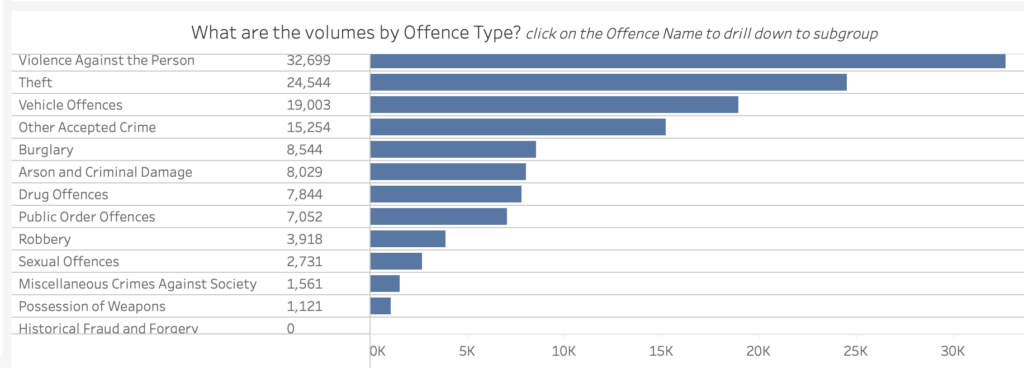

Between January 2018 and December 2022, the MPS recorded 2,962 hate crimes in Waltham Forest but 132,287 other crimes, with the latter broken down as follows:

During this five-year period, therefore, hate crime was always a minor phenomenon, dwarfed by other kinds of crime, and constituting just 2 per cent of the total.

Context (2) hate crime in Waltham Forest v. hate crime elsewhere in London

In a league table of hate crimes per thousand population in 31 London boroughs from January 2018 to December 2022, Waltham Forest does not stand out, ranking joint nineteenth. In other words, it certainly is not a hate crime hot spot.

Context (3) hate crime and police performance

Finally, since the police periodically complain about underfunding, it is worth asking whether the focus on hate crime has impinged on their other responsibilities.

This is difficult to determine, but the signs are not reassuring.

What’s certain, to begin with, is that for some years now police performance in Waltham Forest has been unimpressive.

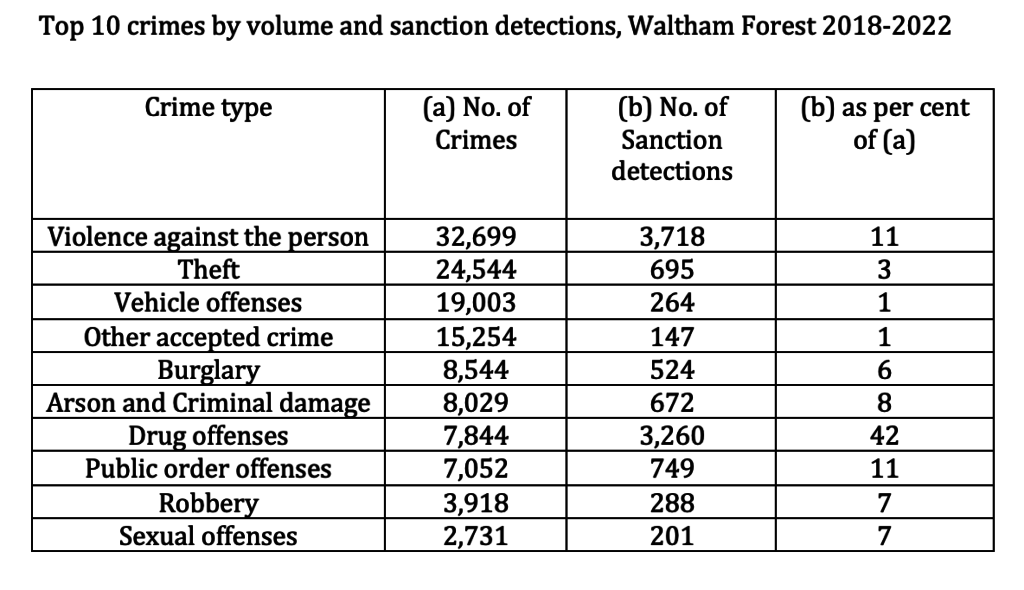

The conventional method of measuring police productivity is to look at sanction detection (SD) rates, broadly speaking ‘the percentage of recorded offences that result in a sanction against the suspect’.

The MPS figures for the top ten crime categories in Waltham Forest are as listed here alongside the SD data:

In seven of the categories, the SD to crime ratios are less than 10 per cent, with only drug offenses being anywhere near the 50 per cent mark, outcomes that can only be called dismal.

Moreover, it’s apparent from the MPS data that SDs in Waltham Forest have fallen over time, with the total SDs per thousand residents index at 8.7 in 2018 but 7.8 per in 2022.

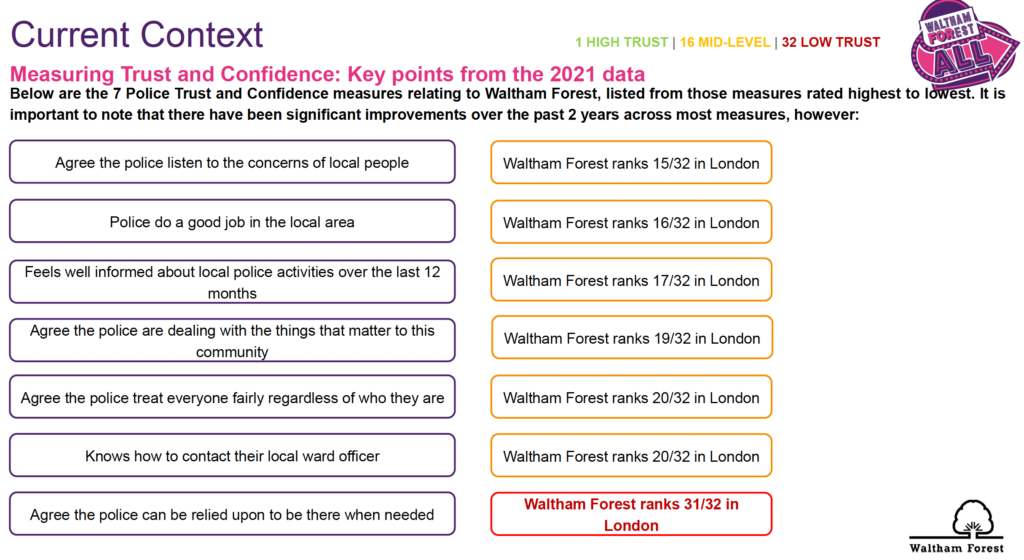

To make matters worse, it seems that, when compared to elsewhere in London, the local police also are not very good at retaining public trust and confidence, as a table that LBWF produced in 2021 indicates:

In short, the police have adopted an extra priority at a time when they are already struggling. Perhaps they have managed the change with ease. But it’s more likely that the upshot has been further stress and strain, and perhaps even operational trade-offs, for example the privileging of hate crime at the expense of other types of crime.

Of course, little is ever said about this in public, as it is designated the exclusive preserve of senior officers. But it surely deserves to be explored further in any future debate about the direction of resourcing.

Conclusion

As the forgoing shows, hate crime in Waltham Forest has been significantly oversold. There are relatively few alleged crimes of this type, even fewer that are verified after investigation, and even fewer still that result in a sanction.

Whether hate crime should, nevertheless, remain a priority is debateable and opinions will differ. But the important point is that any decision one way or the other should not, as at present, be imposed from above, but rather stem from democratic dialogue, involving as many residents as possible, and informed by the full array of the facts rather than a convenient selection.

Conversely, those with an inbuilt interest in talking up the scale of the issue, whether consultants chasing contracts, political activists riding their hobby horses, or caucuses of councillors using the issue for electoral gain, politely should be shown the door.