EXCLUSIVE From 2015 to 2022 the number of senior staff in the Town Hall grew nearly fourfold, the cost of employing them did too, but service levels remained average

What follows looks in greater detail at an earlier post’s revelation (see links) that in the past few years, despite repeatedly complaining about government imposed cuts, LBWF in fact has spent millions more from the public purse appointing expensive senior staff.

To get a better handle on this surprising development, I have analysed the annual series which LBWF publishes about its senior staff (here defined as everyone from the chief executive, paid £217,762 p.a., through the different directors and heads, down to grade PO8, paid £50-55,000 p.a.), focusing particularly on the period 2015 to 2022, when the data was presented in common format (regrettably, a 2023 update has yet to appear).

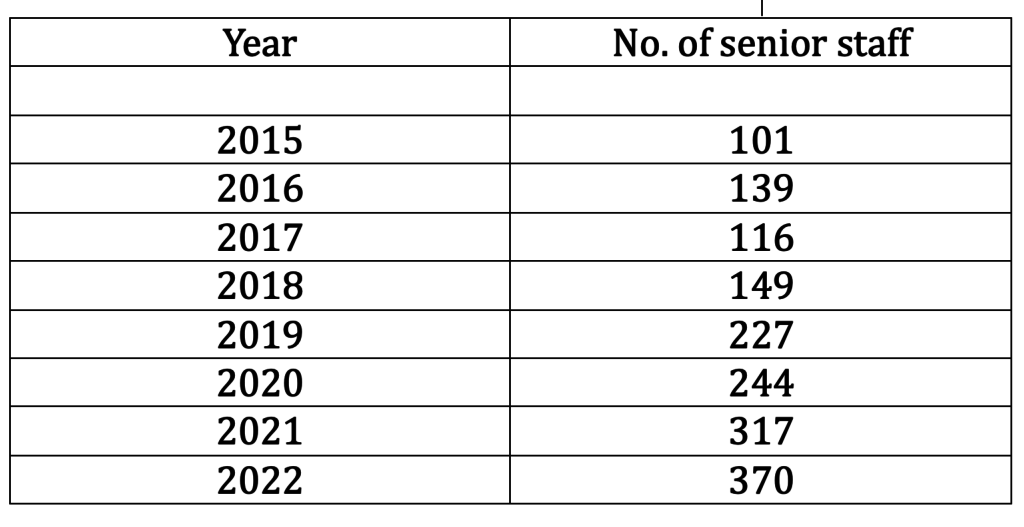

The first finding, and one that jumps off the page, is that, since 2015, the number of senior staff has grown (a) every year bar one, and (b) getting on for fourfold over the period 2015-22 as a whole:

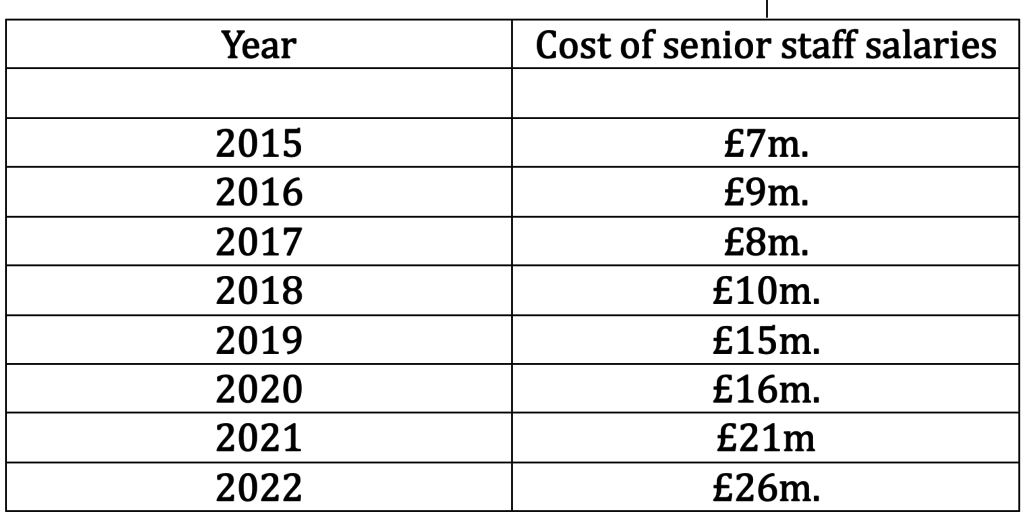

The second finding is that, inevitably, this has cost a serious amount of public money.

Calculating exactly how much is not straightforward, but the following are annual estimates (their method of calculation is described in an endnote):

Not unexpectedly, then, as the number of senior staff has increased, so the cost of their pay has risen in roughly similar proportion.

And to put the 2022 figure, £26m., in perspective, LBWF is currently projecting that this financial year, it will end up with a deficit of £16m., something that is thought concerning enough to justify the launch of a voluntary redundancy programme.

Quite why there has been this expansion remains unclear, largely because the issue has so far attracted very little internal or external comment, let alone informed scrutiny.

Many will claim this is a classic example of empire building, perhaps based upon the old pals act, with the politicians who are supposed to be in charge turning a blind eye in exchange for compliance and loyalty.

A more charitable explanation is that at some point in the recent past LBWF decided it needed substantial extra management resources to function efficiently.

However, if better performance was, and is, the objective, it doesn’t seem to have materialised, as a brief summary of the evidence demonstrates.

One year ago, a survey which used official data for 2016-22, revealed that LBWF was the sixth most complained about council, not in London, but in the whole of England.

As of today, the Office of Local Government (Oflog) performance tool, which rates English councils on 20 metrics covering waste management, planning, adult social care, and corporate finance, reveals that LBWF is rated above the national median in eight cases, but below it in twelve, a less than inspiring overall outcome.

Perhaps most revealing of all, when LBWF Director of Governance and Law, Mark Hynes, addressed staff late last year about the forthcoming redundancies, his presentation included the following admissions (emphasis added):

‘Fear of crime is becoming a more pressing concern for residents, and many do not feel well-connected to their neighbourhood’,

and

‘An increasing number of residents that interact with us directly do not think the Council represents good value for money’.

This suggests that, in Mr. Hynes’ view at least, performance levels may not be flatlining, but actually declining.

During the past decade or so, successive Labour Leaders have continually insisted that, first, Waltham Forest has historically always been treated poorly by the government, and, second, that in addition the cuts experienced across the local authority sector since the Conservatives came to office have added insult to injury.

They have further claimed that, despite the enforced ‘tough choices’, LBWF has sought to ‘progress Labour values’, and do everything possible to ‘provide a fairer future’ for residents.

Few could dispute elements of this narrative. Like all other councils, LBWF has faced challenging financial circumstances.

But when Cllr. Williams next pontificates about the Town Hall’s woes, it might be a good idea if journalists and councillors engage their critical faculties, and ask her why it is that LBWF has recently opted to appoint so many expensive senior staff – why, to give a specific example, as of 1 April 2022 her council was employing 39 staff on £100,000 p.a. and above, plus a further 114 staff on £70,000 to £99,999 p.a., when only a few years before it managed with around a quarter of these numbers.

Endnote: calculating senior staff pay

Please note: (a) LBWF publishes almost all senior staff pay data in terms of bands (e.g., in 2022 the Head of Covid Delivery is listed as earning ‘£70,001 to £75,000’). In every case, I have calculated annual totals using the lower figure in each band (i.e., in this case £70,001), meaning that, because most staff in reality earn sums somewhere between the top and bottom cut-offs, the estimates presented here are significantly below the true figures, perhaps by as much as 5 to 10 per cent; (b) in addition, my estimates (and the LBWF series) do not take account of other employment-related costs accruing to LBWF, such as national insurance and pension payments; and (c) on the other hand, I have not adjusted for inflation.