LBWF spends enormous amounts each year on non-disclosure agreements, but is this justified?

In recent years, and particularly following the Harvey Weinstein scandal, there has been growing unease about the use of non-disclosure agreements (NDAs).

It is widely accepted that NDAs can be appropriate in some circumstances, for example to protect sensitive commercial information.

The worry, however, is that on occasion NDAs appear to have been deployed solely to cover up unlawful or abusive behaviour.

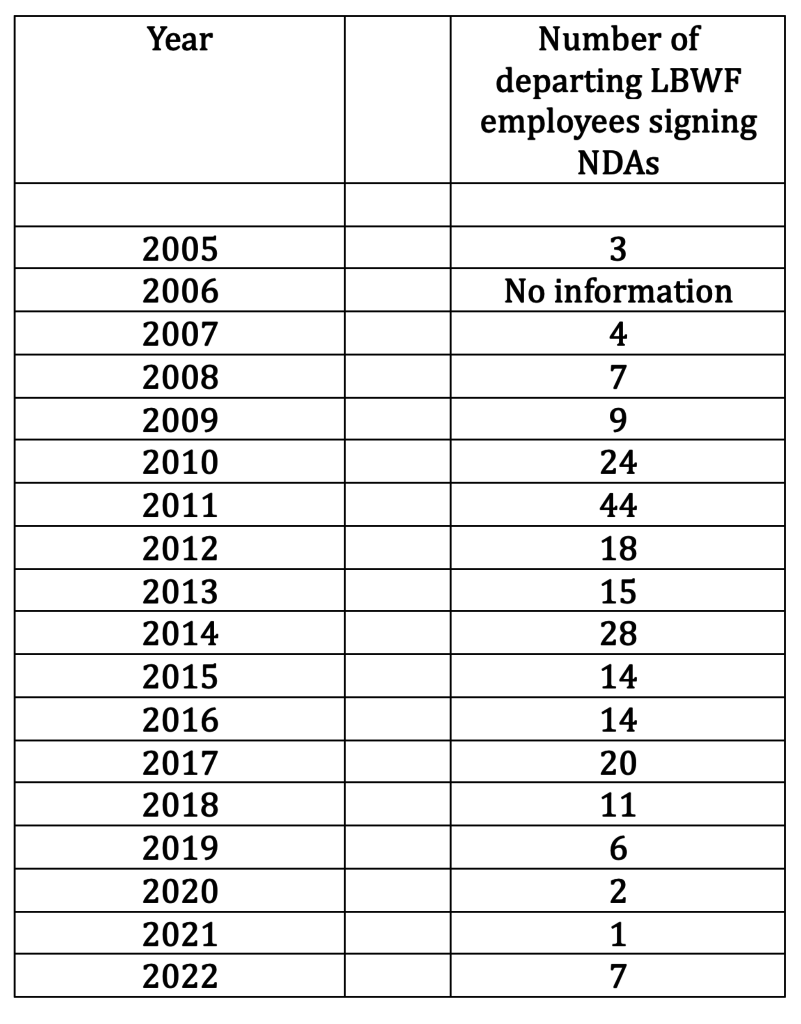

Against this background, it is perhaps surprising to find that LBWF has used NDAs quite extensively, as the following table demonstrates:

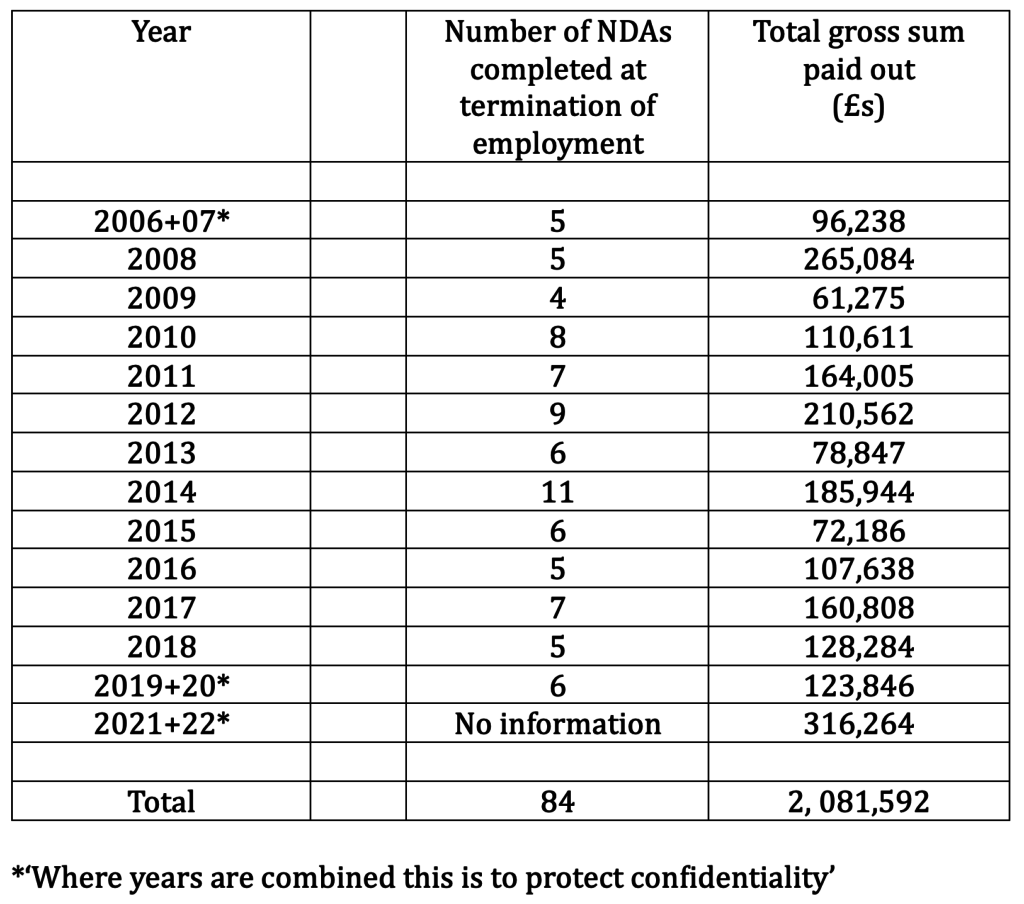

Moreover, this has come at a cost, since a significant proportion of these agreements have been accompanied by compensatory payments, with the annual figures here:

That a total of c. £2.1m has been spent over a seventeen-year period, at an average of £122,447 p.a., suggests that LBWF has seen NDAs as routine, just another HR tool.

But since £2.1m. is a large sum, which could have been channelled to directly benefit residents, and LBWF now continually complains of being short of money, it is worth looking at this issue further. Has LBWF’s recourse to NDAs always been in the public interest?

Doubtless, LBWF will point to the fact that, when put in context, its use of NDAs has been unremarkable, since virtually all its peers have done exactly the same.

At a factual level, this is certainly true. For example, Taxpayers Alliance research which focused on 2016-19 found that (a) of the 408 local authorities that were contacted, all but 45 had at one time or another used NDAs, and (b) some pay outs were even bigger than in Waltham Forest, with those completed by Leicester City Council, for example, costing in total a whopping £531,716.

However, any argument based on the premise that ‘since everybody is doing it, it must be OK’ fails to convince simply because, regardless of Mr. Weinstein’s antics, concerns about the extent and character of NDAs in the UK public sector, not least emanating from professional bodies like the Solicitors Regulation Authority, are long standing, and have persisted right up to the present.

Indeed, as recently as September 2023, the Labour MP Rachael Maskell told the Commons: ‘When I was a union official, I saw many times how compromise agreements were a cheap option to try to buy people off, to move an issue sideways and to protect the perpetrator in the workplace…Whether it is in healthcare, local government—we know it happens there—education or the police and justice system, we know that the issue is pretty prevalent’.

Turning to the data about LBWF specifically, it is, needless to say, impossible to draw any definitive conclusions about legitimacy.

That said, there are certainly one or two straws in the wind.

It is striking to find that an unusually large number of NDAs, and some big pay outs, were completed between 2009 and 2012, as these were years when LBWF was rocked by revelations about its misuse of government funding that should have benefited the poor; the Independent Panel issued a scathing report about leadership failure and lack of transparency in the Town Hall; and behaviour such as the following was by no means unknown:

‘A Waltham Forest senior employee was asked to produce a specification for [a contract]…with the full knowledge of certain more senior individuals in the Council that he was going to join a regeneration company who were going to bid for the work. He produced the specification and sent it to his new company, left the Council and then returned the completed bid back to the Council. It was not the lowest bid and there were no proper evaluation criteria but the contract was still awarded to the company’.

Could it be that LBWF was issuing NDAs to cover up the true magnitude of these scandals, and so protect favoured members of the hierarchy? Or was this all just coincidence?

The situation in 2021 and 2022 is also arresting. LBWF had been completing fewer and fewer NDAs for some time, but there was a sudden uptick in 2022, with payments totalling a third of a million pounds for the two years together, which again raises questions about exactly what was going on.

Of, course there is an irony in all of this which is amusing.

In 2021, the LBWF Leader, Cllr. Clare Coghill, resigned and joined a property developer, one that was part of a corporate group which worked in Waltham Forest.

If ever there was a time when a NDA seemed merited it was surely now. After all, Cllr. Coghill had extensive knowledge of all LBWF’s current operations and future plans, as well as a keen appreciation of its strengths and weaknesses, and real financial circumstances.

Yet since Cllr. Coghill was not an employee of the council, an NDA was out of the question, and there was little or nothing that could be done to stop her sharing information with her new colleagues if she so wished: according to then CEO Martin Esom, if she was found to have disclosed confidential information, the council might consider ‘injunctive relief and damages’, but how could he (or anyone else) possibly know if this had happened?

Doubtless, Ms. Coghill has behaved impeccably throughout, but nevertheless it makes for a suitably Waltham Forest-ish addendum.

PS I am grateful to Michelle Edwards for supplying me with much of the data cited in this post.