Local faith in the police plummets to levels lower than elsewhere in London. Why? Probably because too few criminals are being caught!

It is a striking, though often overlooked fact, that Waltham Forest residents’ trust and confidence in the police has not only declined markedly over recent years, but is also comparatively less favourable than in most other London boroughs.

What follows looks at the dimensions of this unsatisfactory situation, and then turns to discuss its possible causes.

Local trust and confidence in the police: the facts

Each year, the Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime (MOPAC) runs large-scale surveys to measure six metrics about how samples of the public assess the police, borough by borough.

Looking at the data specifically for Waltham Forest, the following emerges.

1.Do you have ‘confidence in the police’?

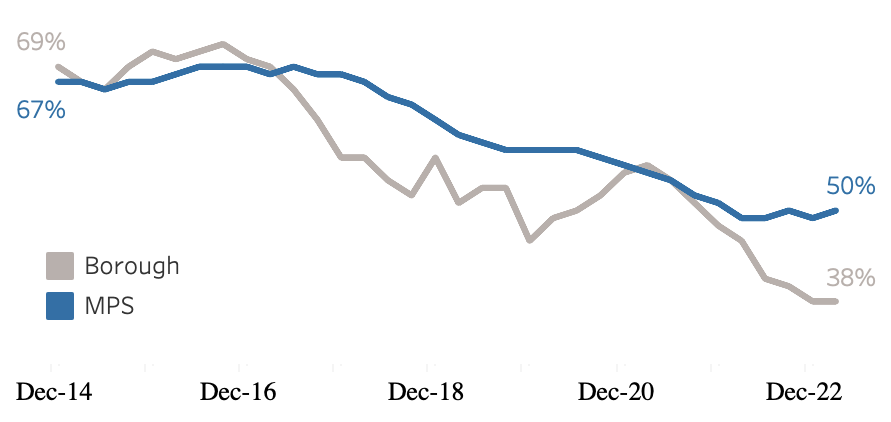

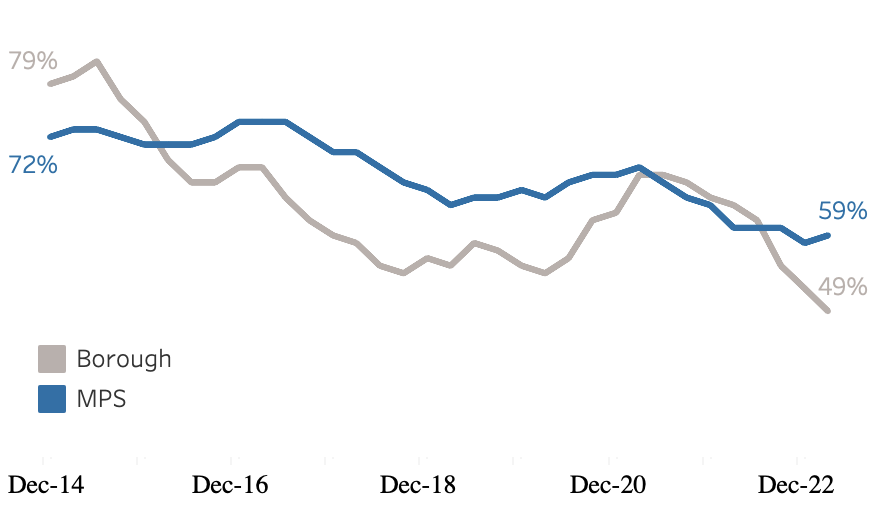

(a) Per cent of residents who have confidence in the police, Waltham Forest v. Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) area average, Dec. 2014-Dec. 2022:

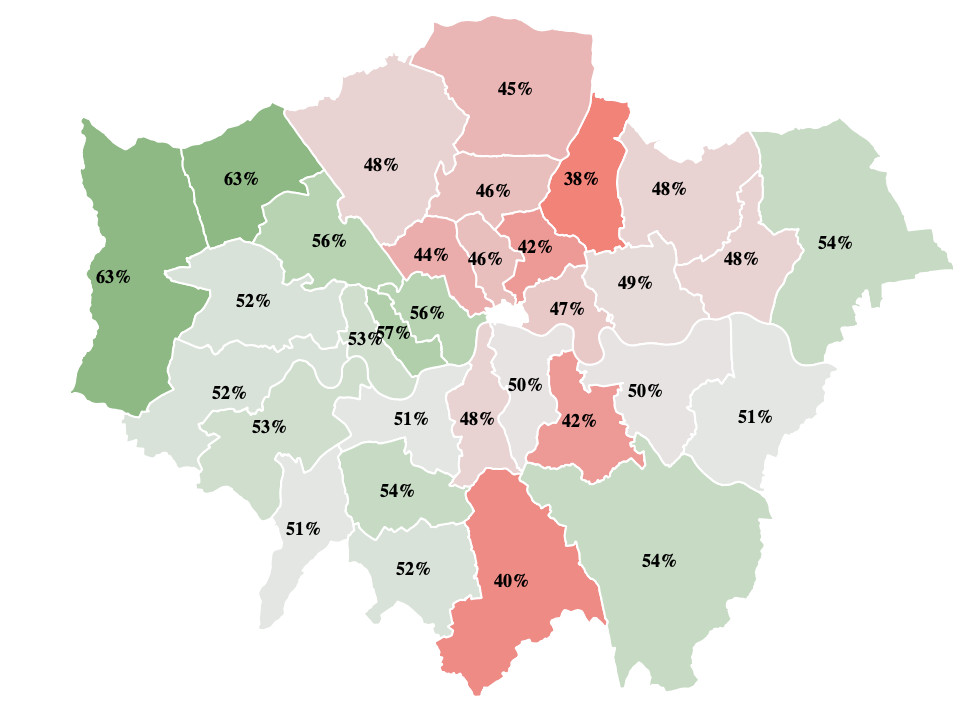

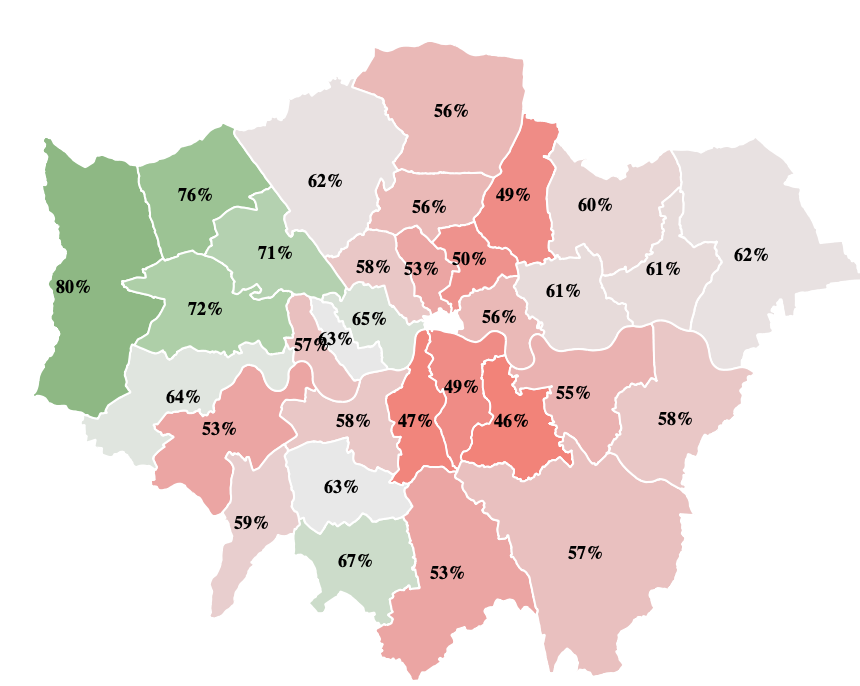

(b) Per cent of residents who have confidence in the police, all London boroughs, rolling 12 months to 2023:

2. Are the police ‘listening to the concerns of local people’?

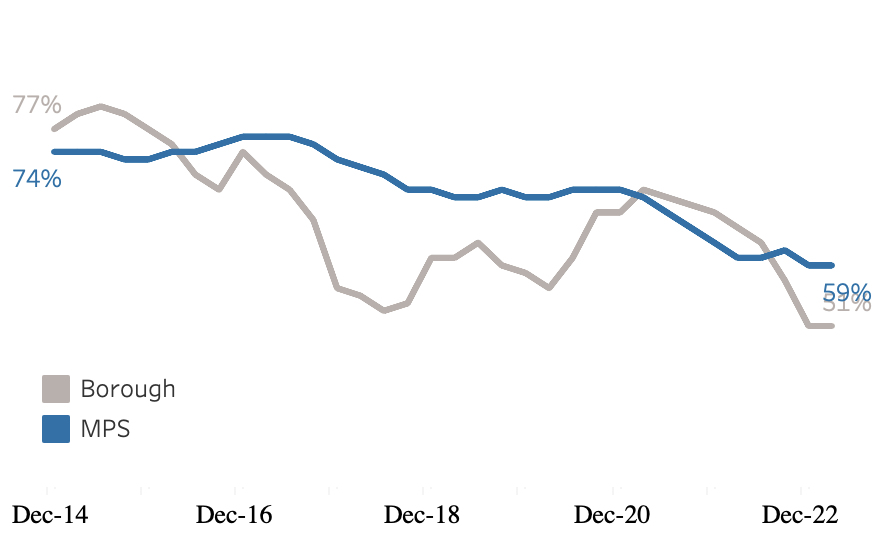

(a) Per cent of residents who agree the police are listening to the concerns of local people, Waltham Forest v. MPS area average, Dec. 2014-Dec. 2022:

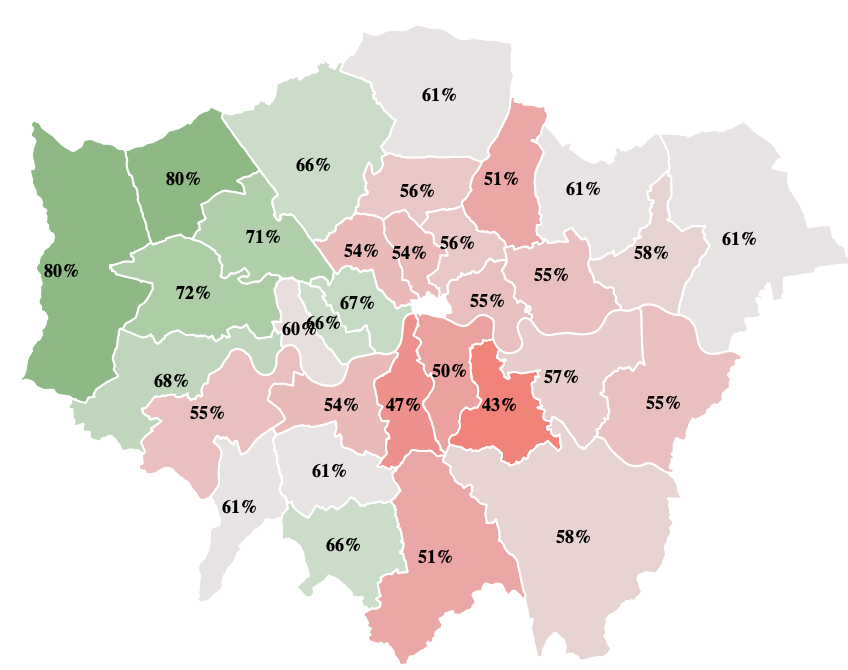

(b) Per cent of residents who agree the police listening to the concerns of local people, all London boroughs, rolling 12 months to March 2023:

3. Are the police ‘dealing with things that matter to the local community’?

(a) Per cent of residents who agree the police are dealing with things that matter to the local community, Waltham Forest v. MPS area average, Dec. 2014-Dec. 2022:

(b) Per cent of residents who agree the police are dealing with things that matter to the local community, all London boroughs, rolling 12 months to March 2023:

In short, Waltham Forest residents’ confidence in the police has fallen sharply since December 2014, as has their faith that the police are listening to, and acting upon, local concerns; and though similar trends are observable all over London, they are more pronounced in Waltham Forest than in all but one or two of the other boroughs.

What has caused this growing sense of dissatisfaction?

Explanations (1) delusion about crime levels

One theory that is fashionable in some parts of the Town Hall is that (for reasons that are unexplained) Waltham Forest residents believe that crime is much more pervasive than it actually is, and it is this misapprehension which feeds the discontent.

It is true that the amount of crime in the borough is unexceptional in pan-London terms.

But whether Waltham Forest residents are especially unrealistic about crime levels is doubtful. On the contrary, when an experienced consultant probed local focus groups in late 2019, he emphasised that, far from being deluded, participants’ perceptions of crime and safety were based on ‘real, lived experience’.

Explanations (2) police performance

A more plausible explanation is that resident’s assessments are rational, and stem in large part from the fact that, especially for those crimes which are popularly believed to be priorities, the police too often fail to find the culprits.

What residents want prioritised is easy to determine, because since 2019-20, MOPAC has annually questioned residents in each London borough about ‘the top three things that the police should be dealing with in your area’, and over this period the first choices for Waltham Forest have remained remarkably consistent, in order, ‘Gun/knife crime’, ‘Drugs and drug-related crime’, ‘Anti-social behaviour’, and ‘Burglary’, with virtually every other type of crime cited far less frequently.

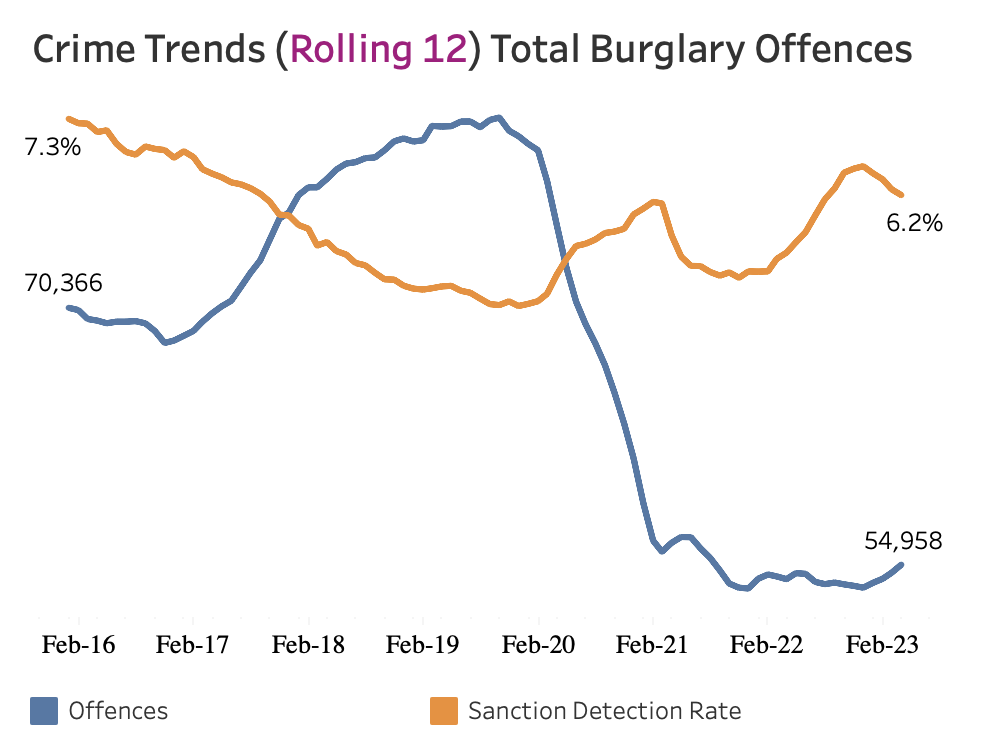

As to police performance, the conventional method of assessment is to look at sanction detection rates (SDRs), sometimes referred to as ‘solved crime rates’.

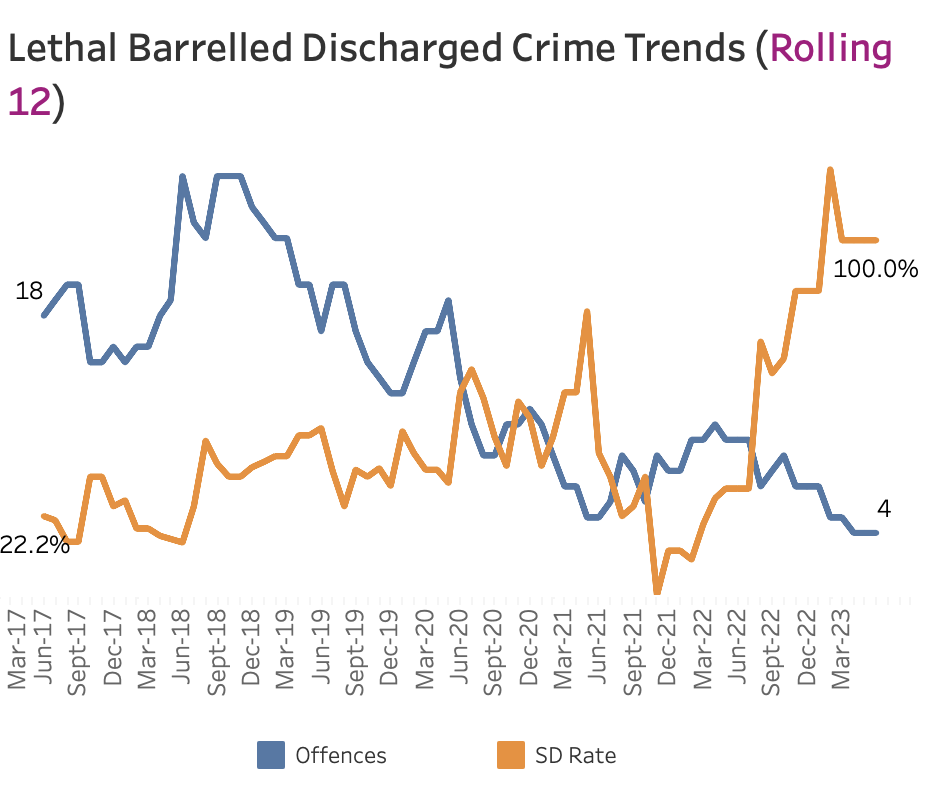

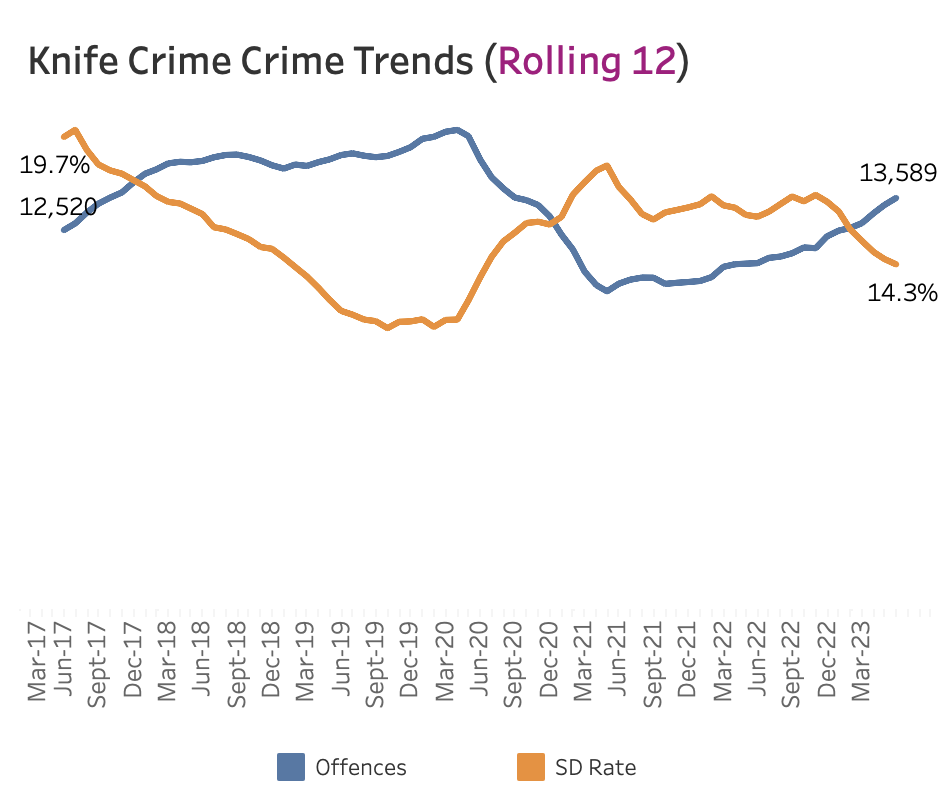

Unfortunately, in this instance, partly because of differing definitions, partly because of data gaps, it is not possible to cite SDRs for all four of the resident’s top priorities, but the following is at least suggestive:

It’s to their credit that the police are good at solving gun crime, but with knife crime and burglary, the story is very different, with the big majority of perpetrators unidentified.

Needless to say, it might be objected that since most residents are unlikely to be familiar with the SDR data in any detail, the latter can hardly be the reason why the police are judged comparatively harshly.

But this is to overlook the fact that crimes which residents consider as priorities will often be widely discussed, rippling out through family, friendship, and workplace networks, meaning that they soon become important ‘signals’, shaping wider public perceptions.

Explanations (3) LBWF and police responses

Finally, the approach to crime adopted by both LBWF and the police is also a factor, because it has only partly connected with residents’ concerns, magnifying disenchantment.

One thing that stands out immediately is the fact that in public discussion neither party shows much interest in referencing SDR data, and some councillors appear not to know that it exists.

More worrying still, in official pronouncements, accurate statistics of any kind are often notable by their absence, or distorted in order to support the user’s argument, one common trick being to compare a peak and later trough in the same year, and assert that crime X has declined by Y per cent, all the time ignoring the fact that year on year crime X is actually rising.

The two organisation’s stated priorities also are questionable. As previous posts have reported, both LBWF and the police have put significant resources into combating hate crime, despite the evidence revealing it to be a small-scale phenomenon that doesn’t much worry residents, with the MOPAC surveys showing that just 2 per cent of local residents at best see it as one of their three top priorities. Yet by contrast, if there has been a programme to specifically address burglary, it’s been kept well under wraps.

Further, even where LBWF and the police have responded to popular concerns, for instance over knife crime, the situation is not necessarily satisfactory. LBWF launched the Violence Reduction Partnership (VRP) in late 2018, based on a public health approach to the problem, but whether it is a success or not remains unclear. The council’s website features a list of participating organisations, but little about their contracted and actual outputs. An annual report appeared in 2019, but has not been replicated since. There is a lack of transparency about how much money is being spent, and where it is coming from (which happened, too, with the VRP’s predecessor, the Gang Prevention Programme). As is often the case in Waltham Forest, the only way to get the facts is by recourse to the Freedom of Information Act.

Meanwhile, opportunities for residents to directly get involved in debating crime are floundering. In the recent past, the Safer Neighbourhood Board attracted hundreds to its meetings, but subsequently (and despite the supposed guidance of senior councillors including Karen Bellamy and Roy Berg, plus MOPAC representatives) poor leadership, infighting, and complaints about misogyny, have precipitated a total collapse. The Board’s future is now subject to a review, and hangs in the balance.

That leaves the police ward panels (PWP). It is true that some of these work well, meet regularly, and take residents seriously, but this is by no means guaranteed. There has been some confusion about who is allowed to attend. The quality of the chairs (always an important variable) differs. A few years ago, one was notorious for proudly and loudly stating he was innumerate (though, as might be predicted, this didn’t stop LBWF from giving him preferment). Perhaps worse still, publicity about meetings is dismal. As for virtually every other ward, the Cann Hall neighbourhood police team’s website as of today states only that ‘There are no meetings or events scheduled’. Turning to the relevant part of the LBWF website, it gives no indication that PWP meetings even occur, and anyway hasn’t been updated since February 2023. There could hardly be a more vivid illustration of the value which is put on resident participation.

Afterword

In a long interview with the Waltham Forest Echo in April of this year, Detective Chief Superintendent Simon Crick, who heads the Newham and Waltham Forest police force, spends a good deal of time bemoaning the fact that he and his colleagues are not getting over their side of the story. ‘“One thing we struggle with is communicating with residents”’, he says, and continues: ‘“How can I expect people to have trust and confidence in us if we are not communicating what we are doing in an effective way?”’.

If he really thinks that communication is the heart of the problem, it would appear that he, too, has not recently checked the SDR data.