LBWF and public-private partnerships: (1) NPS London Ltd.

As this blog has previously noted, LBWF is now involved in extending its public-private partnerships, and so it is timely to look at some previous examples of similar initiatives, in order to discover what lessons can be learnt. A subsequent post will return to the vexed history of North London Ltd., while what follows focuses on NPS London Ltd. (NPSL), jointly owned by LBWF and NPS Property Consultants Ltd. (a subsidiary of Norse Group Ltd., itself the child of Norfolk County Council).

NPSL was formed in 2007, taking over what was previously LBWF’s in-house building consultancy service, with the staff TUPE-ed over. Subsequently, NPSL has been involved in a number of big LBWF projects, in particular the school building programme, providing specialist input such as surveying, architectural design, energy and sustainability management, quality inspection, water hygiene management, and asbestos advice. In 2015, the Cabinet agreed to extend NPSL’s original ten-year service agreement to 2022; and discussions are currently underway ‘to explore the opportunity of further outsourcing of property related services to our joint venture’.

At first sight, this appears to be a mutually advantageous arrangement, one that delivers benefits to both sides. NPSL gains because it enjoys exclusive supplier status. For its part, LBWF is unburdened of, for example, pension liabilities; has some influence over service charges (which are supposed to be regularly benchmarked to ensure value for money); and receives a half share each time the company delivers an annual operating out-turn which is in profit.

Underpinning all of this, LBWF also is involved at Board level. Of NPSL’s ten shares, eight are owned by NPS Property Consultants Ltd., but LBWF has the remainder, allowing it two directorships. Over the years, this provision has been taken seriously, and incumbents have included such luminaries as LBWF Chief Executive Martin Esom (2007-08, 2010-14); past and present Leaders Chris Robbins (2007-09) and Clare Coghill (2014-17); and senior Labour councillors Afzal Akram (2010-12), Simon Miller (2017-present), Mark Rusling (2012-14), and Terry Wheeler (2009-11).

So how have these arrangements worked out in practice?

Taking narrow financial matters first, it does seem that, in the early years at least, LBWF benefited. Benchmarking of NPSL’s service charges in 2014 concluded that they offered ‘fair value’. Moreover, since the company continued to earn operating profits, LBWF received regular cash bonuses, totaling £276,000 between 2011 and 2014.

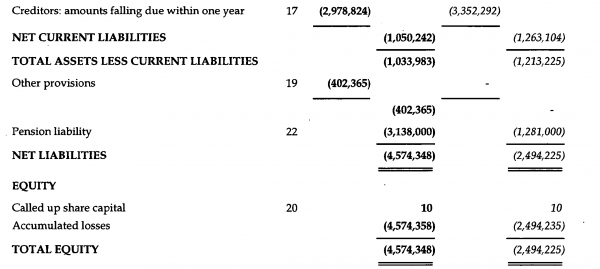

Yet more recently, the situation has become a good deal less propitious. Local authority spending in general has fallen, and so NPSL has found trading more difficult. The company has cut its staff by over a quarter, and returned consecutive after-tax loses. Turning to operating out-turns specifically, these were positive in some years, but negative in others, for instance 2016-17, when the loss was £326,405. Meanwhile, NPSL’s overall financial health has also deteriorated, as its latest accounts demonstrate:

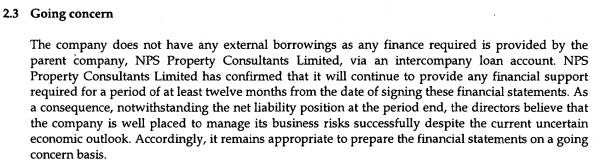

Accordingly, in each of the past two years, the directors have felt it necessary to add this note of reassurance:

It will be interesting to see what happens next. When questioned in 2012, Mr. Esom advised ‘With regard to any losses, these relate to the Company NPS London Ltd and are not shared by LBWF’ (though whether this safeguard is contactually guaranteed is unclear). And it may be that even if poor performance continues, and net liabilities increase further, the NPS side will keep to its current policy and provide sufficient support. But it is possible, too, that LBWF finds itself left holding the baby.

Concern about such matters is magnified because of doubts about whether LBWF’s influence over NPSL affairs is necessarily as effective as it ought to be. The two organisations are certainly closely bound together, with the board links, already described, to some extent mirrored at officer level. Thus, the Marina Dimopoulou who as LBWF ‘Assistant Director, Asset Management and Delivery’ authored the 2015 Cabinet paper for Cllr Clare Coghill proposing NPSL’s contract extension is presumably the same Marina Dimopoulou who NPSL today describes as its ‘Operations Director’.

But whether this intertwining is necessarily the most effective way of securing LBWF’s interests is open to question. NPSL’s delivery record is in some ways impressive, though also not without significant blemishes. For example, NPSL was LBWF’s asbestos adviser at the time of the Town Hall asbestos contamination scandal in 2012, which of course resulted in a court conviction and fine of £66,000 (plus £16,000 costs); and in 2017 NPSL was itself found guilty of a further historic asbestos related offence, this time at St. Mary’s Primary School in Walthamstow, and fined £370,000 (with £32,000 costs).

More worryingly still, as documented in the posts linked below, when requests have been made to see the paperwork that records LBWF-NPSL interactions, including at the highest level, the answer has come back – astonishingly – that such material either does not exist or is purely ‘verbal’.

In sum, this is clearly a case that merits further scrutiny, and updates will appear shortly.