LBWF and the anti-terrorist Prevent programme: is it wise to keep it in the closet?

In early June of this year, I asked LBWF under the Freedom of Information Act for a list of its current Prevent contracts, with for each its start and finish dates, the name of the contractor, the value of the contract, and a brief description of what the contract aims to achieve.

A few days ago, my request was refused, with LBWF arguing as follows:

‘Waltham Forest Council recognises the public interest in transparency and openness in local government; and in the context of this Freedom of Information request, such openness would increase public understanding and inform public debate about the aims and objectives of Prevent work in the borough. Additionally, disclosure would raise public awareness of the activities government undertakes to prevent terrorism and this type of information demonstrates openness and accountability in how resources are used in combating crime.

However the need for openness and transparency needs to be carefully considered and balanced against our responsibility to safeguard the personal safety of Prevent providers, their staff and clients, and also to consider any implication this type of disclosure would have on Prevent activity in the borough and in the rest of the country.

Releasing this material could allow information about organisations and individuals who are, or have been engaged in the delivery and support of a range of activities to prevent terrorism to be determined; this could undermine the objectives of the Programme and could put individuals at risk of injury or harm from those who support terrorism and seek to damage the United Kingdom’s interests and harm individuals within its communities. Identifying where this targeted work is ongoing will allow counter action to be taken against those who are working with those individuals, and to target vulnerable individuals themselves.

We find the balance of public interest in favour of withholding the information requested, therefore this request is exempt from disclosure by virtue of sections 24(1) (National Security) and 38(1)(b) (Health and Safety) of the FOI Act.’

To what extent is this refusal merited? First, some background.

The Prevent programme is one of four elements which make up Contest, the government’s anti-terrorism strategy, and aims to respond to ‘the ideological challenge we face from terrorism and aspects of extremism, and the threat we face from those who promote these views’; provide ‘practical help to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism and ensure they are given appropriate advice and support’; and work ‘with a wide range of sectors (including education, criminal justice, faith, charities, online and health) where there are risks of radicalisation that we need to deal with’. According to a government paper, it uses a range of measures to challenge extremism, including:

- [stopping] ‘apologists for terrorism and extremism from travelling to this country’;

- ‘giving guidance to local authorities and institutions to understand the threat from extremism and the statutory powers available to them to challenge extremist speakers’;

- ‘funding a specialist police unit which works to remove online content that breaches terrorist legislation’;

- ‘supporting community based campaigns and activity which can effectively rebut terrorist and extremist propaganda and offer alternative views to our most vulnerable target audiences – in this context we work with a range of civil society organisations’; and

- ‘supporting people who are at risk of being drawn into terrorist activity through the Channel process, which involves several agencies working together to give individuals access to services such as health and education, specialist mentoring and diversionary activities’.

(https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/2010-to-2015-government-policy-counter-terrorism/2010-to-2015-government-policy-counter-terrorism)

Based upon past experience and recent statements by LBWF Chief Executive Martin Esom at a City Hall hearing, it is likely that LBWF is receiving government money for running programmes in categories 4 and 5 on this list, for example ‘a very broad-brush intervention in all schools so that we raise awareness of the issue with children and give them…[a] counter-narrative’ (City Hall Police and Crime Committee, 19 May 2015 Appendix 1: Transcript of Agenda Item 9 – Preventing Extremism, p. 6).

So, is LBWF right that such activity should be kept secret? Let us begin by taking this contention at face value.

The first thing to remark upon is that LBWF’s stance lacks consistency. For ten minutes with Google is enough to reveal the identity of the local Prevent coordinator, and at least two, and possibly three, providers. So, if the overriding objective really is to keep Prevent in Waltham Forest out of the public eye, it has not been particularly successful.

A second response is prompted by a bit of historical context. In 2009-10 I had a prolonged correspondence with LBWF about Prevent, and this led to it providing me with a good deal of detailed information about what was going on, some of which (as we shall see) also found its way into both the Waltham Forest Guardian and Private Eye. If there was no great concern about secrecy then, what is it that has changed so much in the intervening years?

It is unarguable that Islamists who are ill-disposed or actively hostile to democratic liberal values and moderation have been a feature of the local scene for a considerable number of years. As long ago as 2007, the Institute of Community Cohesion observed:

‘We gained the impression that in the past there had been significant activity and support in the Borough for groups which are now proscribed, such as Al Muhajiroon and Al Ghuraba. Former prominent members of such groups are still active in the Borough. We also heard of activity by Jihadi Groups (in the past) openly recruiting in the Borough; and from the focus groups and some of the people we met about the way religious extremist groups targeted young people, for example by leafleting outside schools and colleges. Hizb Ut Tahrir (HT) are involved in community initiatives and state that they are committed to a strict non-violent political ideology. However we heard from members of the Muslim communities in the Borough, that HT sometimes sent out “mixed messages”’ (Institute of Community Cohesion, Breaking Down the ‘Walls of Silence’ (2007), p.18).

Five years later, just before the 2012 Olympics, the Guardian reported:

‘According to a council paper, the CTLP [counter-terrorism local profile] reported “a high-level threat [emphasis added] of AQ-inspired extremism from males aged between 20 and 38. The individuals of interest to the police are predominantly British-born second- and third-generation migrants from south-east Asia. There is also interest from a number of Middle Eastern political movements and AQ affiliated groups from north Africa”’ (13 February 2012).

If the people and groups have been largely a constant, by definition what must have changed, as the Council sees it, is their propensity to either threaten or commit violence, plus the scope of their targets. So whereas five years ago those going about their lawful business in terms of Prevent were safe from harm, now they are not.

The security services may have credible evidence of this new belligerence, true, but it is also important to note that while internecine arguments between Muslims on occasion have degenerated into a depressing though by now predictable cacophony of death threats, as far as I can see there is not a single case on the public record in Waltham Forest of similar anger being vented at professionals in service of the wider community.

But the bigger point, surely, is that, if the situation really has degenerated so drastically, then LBWF has a responsibility to honestly tell us so, because we will have reached a new nadir, and need an urgent debate about how to respond. However, that neither LBWF nor any other responsible person or body has so far come forward with this kind of evaluation of course makes me wonder.

My concern is increased by looking at other scattered evidence which questions LBWF’s competence in countering extremism. Consider the following:

1. In 2007, a detailed report concluded:

‘It is to be expected – and indeed applauded – that public libraries in areas with large Muslim populations should be receptive and responsive to the interests of local people. However it now appears that because of mistakes by library staff, or the presence of ideologues in the library system, a number of publicly-funded libraries – in Tower Hamlets, Waltham Forest, Birmingham and Blackburn – now stock excessively large collections of certain Islamic texts designed to incite hatred and violence’ (James Brandon and Douglas Murray, Hate on the State. How British libraries encourage Islamic extremism (Centre for Social Cohesion, 2007), p.32).

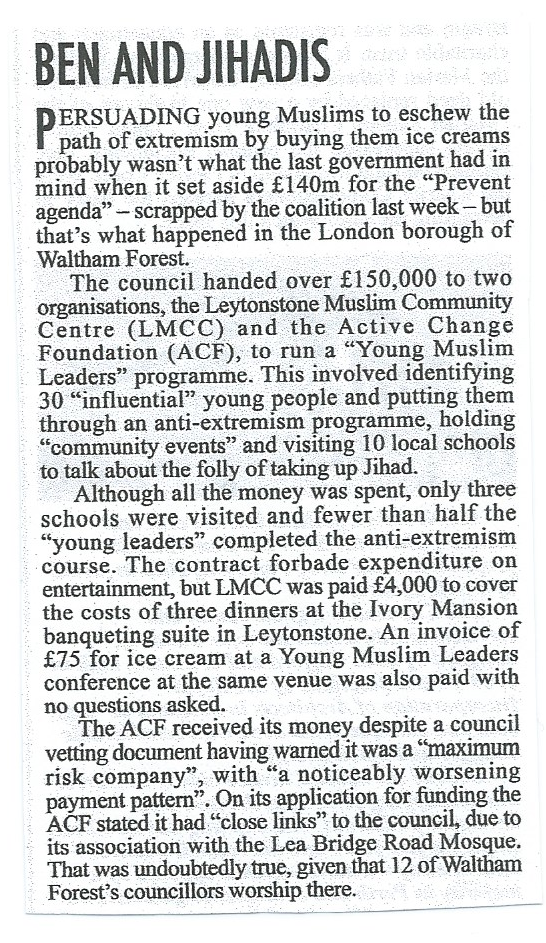

2. In 2008-10, some councillors and national Labour politicians repeatedly touted the Prevent programme in Waltham Forest as a model for others to follow, but the Waltham Forest Guardian and Private Eye exposed a very different story, with the latter for example reporting as follows:

(Private Eye, no. 1267, 23 July-5 August 2010. Incidentally, the reference to ‘close links’ at the end of this piece is based upon the 2007 Institute of Community Cohesion report previously cited, which observed at paragraph 3.1.5: ‘There are 12 councillors from the Muslim communities in Waltham Forest. However, these councillors do not reflect the diversity of the communities in the borough – associated as they all are with the…Lea Bridge Road Mosque’).

3. In January 2015, the investigative reporter Andrew Gilligan recounted the following:

‘Last November, in Leyton, east London, there was a public reading of the creed of Muhammad bin Abdul Wahhab, founder of the ultra-conservative interpretation of Islam known as Wahhabism – seen by many as a wellspring of terror. The event took place at the Active Change Foundation, one of the Government’s key partners in Channel. Men and women were ordered to enter the building by separate doors. Hanif Qadir, founder of the Active Change Foundation, is not viewed as an extremist by other providers. “It’s just a business for him,” said one. But speaking to The Telegraph, Mr Qadir vigorously defended the Wahhabi event and the segregation. “Separate entrances for men and women is part of our religion. That just tells you how ignorant you are in understanding our religion,” he said, before putting down the phone’ (Daily Telegraph, 11 January 2015).

4. In May 2015, Martin Esom, LBWF Chief Executive, told a hearing at City Hall: ‘before Christmas I had a deputation of councillors that came to see me about Prevent and how uneasy they felt about the whole programme in the borough’ (City Hall Police and Crime Committee, op.cit, p.3). One reputable source tells me that this neutral sounding description hides a less palatable truth. The deputation was exclusively Muslim, and the ‘uneasiness’ was tinged with sectarianism, the objective of which was to persuade Mr. Esom that Prevent should be re-focused, principally at Shia sects, and Ahmadis.

What makes such evidence all the more compelling is that (as previous posts have shown) LBWF has a long history of spin, what might be termed ‘the Emperor’s new clothes’ approach to public communication; a track record of what appears to be pork barrel politics, with councillors intervening in funding allocations; and a very poor record of spending public money proficiently.

With this in mind, it is at least possible that LBWF’s current unwillingness to discuss its Prevent expenditure is, at bottom, less to do with security threats, and much more to do with anxiety that its blundering and shenanigans may be exposed again to public ridicule, of course in turn threatening the gravy train that chugs around the offices of the Town Hall’s upper echelons.

However, even if none of my suspicions turn out to be justified, I still think LBWF has made the wrong decision about my request, for the following very straightforward reasons. It is well established that the fight against terrorism must necessarily take many forms and proceed at various levels. Action to enforce the law will always be crucial. But terrorism, like all serious crime, in the end cannot be ‘policed away’, and there will always be a need to win the hearts and minds of those who constitute the law abiding majority. This means reassuring them that action to root out wrongdoing is being taken, that public money is being spent wisely, and that the whole process is proportionate and fair. Hiding Prevent in a dark corner, therefore, is self-defeating. It only increases suspicion, and opens the door to those whose aim is to spread dissension (and there are plenty of them).

For all these reasons, I will be appealing LBWF’s decision.